[This is an extract from my book My Midsummer Morning]

Born of Frustration

I have been a father for seven years. It has been the hardest journey of my life.

On my wedding day, such a fullness of emotion. This was truly what it felt like to love, to commit. But that was pulverised by the birth of my children, revealing new depths of devotion to me and an astonishing ferocity of love. The old conundrum of whether you would save someone’s life at the cost of your own does not apply to your offspring. No question. I treasure my children’s lives far above my own.

But here my difficulties began. For I still cherished my own life. And though I would leap heroically in front of a train for my children, I was unwilling to make the less glamorous daily sacrifices that parenting requires. I wanted to remain me. But that no longer felt possible. My life consumed by our life.

I am not the first parent to feel this way and don’t wish to overplay the wrangling of a privileged soul’s midlife crisis, though I was convinced mine was both original and unique. I am a lucky man. I grew up with a loving family in a wealthy liberal democracy. I have qualifications and can easily find work. I have travelled the world. I get paid for my hobbies. I married the woman I loved and together we have two healthy children. If they made me so happy, why was I so sad?

Adventure was incompatible with settling down for many reasons, even leaving aside the type of personality likely to seek adventure in the first place. For most, competence in their profession increases with age. But mine depended upon being a youthful vagabond. Prospects decline with time. Years of domesticity felt like career suicide after I had grafted for so long to make it work. I knew I was privileged to even entertain the thought of doing something different with my life. But many who condemn me as a spoiled Peter Pan could have made the same choices. But they did not through fear or convention or an insufficient capacity for wonder. I have worked extremely hard to try to make something special of my time. Many people find relief from the stresses of life through their hobbies. As they grow older these change, football traded for something easier on the knees. Time-consuming hobbies pause during the baby years. All this is generally accepted, bar a little wistful grumbling. But my hobby was my career. My hobby, my work, my life: everything was the same thing. It was me. I could not compartmentalise things, swap pieces, or pause for a decade. One small baby upset the balance of everything.

A generation ago my masculine desire to remain unshackled would have been relatively unencumbered by fatherhood. My wife would have stayed at home, caring for the children, while I went out to put food on the table and a roof over our head (and get my adventure fix at the same time). When I returned for a bedtime cuddle and play with the kids, she would have tied a pretty ribbon in her hair and had dinner on the table. Such an arrangement would have suited me magnificently! But society has evolved. Sarah has her own career, far more successful than mine, and I love her for that. She is ambitious, intelligent, hard-working, and had no intention of stopping. Nor did I want her to. But like most families today it meant we had many plates to juggle and life was stressful. Besides, I wanted to be around my children, to be a big part of their growing up. I wanted it, I just couldn’t handle it.

The best adventures involve fine margins and grave consequences. There has to be a tacit willingness to court disaster. Not many job descriptions include that. But my attitude to risk changed significantly with fatherhood. I still craved difficulty but abhorred danger. Adventurers each justify their actions on different levels, but I experienced overwhelming guilt rowing the Atlantic having left behind my toddler, baby and wife. A magnificent jape if all went well, a fine story for the grandkids. A stupid fuckup should it widow Sarah and leave my children fatherless. If I had been a salesman it would have been accepted that I needed be away from home for days at a stretch, driving round the country. But the way I earned my living, going away to write an article or make a film, involved doing fun things in beautiful places. Everyone just thought I was a selfish, lazy skiver.So now the conundrum of how to be an ‘Adventurer’ without doing any actual adventures weighed heavily on me, both practically and for my self-respect.

I had lost the carefree liberty to sling a pack on my back, shove my passport in my pocket, and go. I felt like a prisoner and resented it. I don’t think I had a sense of entitlement to my way of life, but others may disagree! Maybe it was because my life had been so focussed on pushing myself hard, trying to fulfil my potential, exploring the world, I found the comedown to the routine of small babies harder than most. I also spent a lot of time amongst similarly highly motivated people with few commitments in their life. Comparing myself to them I felt the relative deprivation acutely. I knew my life was far better than most people’s on earth, but you skew your comparisons to those you associate with. I could not sustain the lifestyle that was approved of in the society I associated myself with. I hated my life as much as I loved my children. I turned mean and sullen. Unkind to those I loved the most, I was present but emotionally unavailable. I made Sarah’s life a misery, souring the joy of motherhood, offering no sympathy for her struggles or helping with her dreams. I was looking for somebody to blame for my life rather than myself. That was invariably Sarah. Instead of building a new identity, I chose to wallow. There were times of acceptance, laughter and joy amidst it all, of course. But there were too many occasions when I came damn close to walking out, slamming the door as hard as I could and never looking back. Only a sense of responsibility held me back. Kept me rocking cradles, warming milk bottles, catatonic.

I earned money as a speaker, getting paid to talk about living adventurously. I was talking a good life, but I was not living one. I flew to Texas to speak at a big conference. A thousand people excited to hear my stories of derring-do. Treated me to business class. But I was a fraud. I got smashed on the plane, fancy red wine and Billy Bragg on repeat. Landed feeling worse than everyone back in Economy class. I hated dredging up my old stories, telling audiences about my glory days, what I used to do, who I used to be. At every single conference, every social event I was asked, “what adventure are you planning next?” And I wanted to scream because “nothing” was not an acceptable answer, for them or for me.

What was I actually doing? I was doing what most parents of young children do. Rushing to get to nursery on time, scrabbling to squeeze in some writing, dashing back for the kids’ tea, bath and bed routine. There’s nothing wrong with any of this. It is real grown-up life. But I craved a life of contrast and variety. A freezing Alpine dawn makes a warm-lie in all the cosier, flopping on the sofa is only a pleasure after a cold wet day in the hills. A month suffering on the Atlantic Ocean or lying on the toy room floor playing Lego both become more appealing following the other.

“It’s only a phase,” I would hear. “Give it five, ten, twenty years and then we’ll get our own lives back.”

Many people – the pragmatic, glass-half-full type – cope with this. Sarah is one of those content optimists. The small victories, the joys, the memories and the anticipations outweigh the drudgery and the passing of time sufficiently to leave their scales tilted towards a life adequately well-lived. I envy their happiness. But I could only feel appalled by the galloping of years. Time slips away. Some called me brave for my adventures, but I did not have the courage for submission, to reconcile my life, to give it purpose and value. Perhaps I was greedy. Perhaps I was just a moaning, spoiled man.

Parenthood fitted neatly into some of my friends’ lives. It made them busy and tired, certainly, but they could juggle careers, marriages, and children and have it all. This group radiated joy. Other new parents underwent a metamorphosis. Wilfully sloughing off their old lives, they emerged as something new, a creature that was, in its entirety, a parent and nothing else. Everything else discarded. The child their project and their only topic of conversation. I am afraid they are too one-dimensional for me to enjoy their company any longer. I know now, looking back, that there are others who seemed to be holding everything together happily but beneath the surface were living lives of quiet desperation like me. I did not notice or realise. It is symptomatic of the state of mind that I was in that I was unable to see, or did not look, beyond my own caged and snarling frustrations.

Meanwhile my friends from the adventure half of my life had no kids. They were gallivanting around the globe, fulfilling dreams, living life, writing books, or even just posting photos of glorious morning runs up their local mountain. The ease of drawing superficial but damning comparisons between your own drudgery and the polished, curated best bits of someone else’s online life has dangers that I am acutely aware of from both sides. I was jealous. They were out there, living like lions, whilst I was festering here in damp, drizzly commuter-land, a dead donkey. I was nagged by insecurities that people would think less of me now my adventures had dried up. The ancient Greeks called this kleos, not only renown but the importance of what others would hear about you and your feats. Achilles faced the choice between the brief dazzling kleos of being a great warrior or the long anonymity of a peaceful life at home with his wife and son. I had always thought he picked the wrong destiny. But now I yearned for the same, to burn, burn, burn across the stars.

As the world raced on without me I looked for ways to cope. I signed up for an Ironman triathlon. Training opportunities were inevitably constrained by looking after the kids. I knew this and was willing to accept scraping through the race rather than doing my best. But one Sunday, sprinting in fury through a tiny ride snatched between the morning childcare and an afternoon kiddy party, I cracked. I jumped off my bike at the top of a hill, flung the stupid bike over a hedge and howled at the sky before crumpling to the verge.

“FUUUUUUUUUUUUUUCK!”

When the tears had cried themselves out, I sheepishly looked around to see whether anyone other than the cows had been watching me. Then I squeezed awkwardly through the hedge in my clumpy cycling shoes, extracted my bike from the field, straightened the handlebars, and cycled slowly back down the hill and home to cancel my race entry. I was learning that lowering my aspirations was the best way to reduce the disappointments and conflict. If I did not have plans or dreams they could not be crushed. I mourned the loss of freedom, confidence and time, the three things that Laurie considered his success with Cider with Rosie bought him. I made myself wilfully numb, removing myself from all decisions, traipsing listlessly through the routine, training myself not to feel, not to think. Only by giving up on my life did it seem possible to live. I willed the minutes to crawl by, heavy hearted as my best years flashed past.

I raged the damp streets on my way to the gym. I’md never liked gyms, preferring running outdoors, but I didn’t run properly anymore. Dodging dog shit down industrial farm tracks made me miss the wild places too much. I turned to the gym as an outlet for my festering resentments and my monotonous life, picking up heavy stuff, throwing it back down again. But gyms are boring when you have nothing to train for anymore. So every few months I’md tire of deadlifts and turn instead to beer, slurping cans on the sofa, watching my life slide out of view. Everything in life I seem to do to extremes, whether that is expeditions or exercise, or anaesthetising boozing.

I lingered late in cities after my talks, inhaling the energy, welcoming the space and time by myself, the freedom of nothing left to lose. Pubs by myself. Knocking them back. Last orders. Spicy chicken wings slouched on the pavement. Newsagent lagers on the last train home, inuring myself to what awaited. But what awaited, when I finally steeled myself to open the front door after sobbing outside in the darkness, were the three people I loved more than anything in the world. Yet I couldn’t stand it. There was an insanity crushing my mind.

For years I had prided myself on being hard. This is a textbook defence against softness. Fractured bones grow back stronger, protecting themselves. I grew up ordinary and unremarkable but I wanted to be more than that, craving success and recognition. Only when I discovered the world of endurance did I find something that might help me stand out. I would never be the fastest, but I would not quit. I would never win a fight, but nor would I lose. You might beat me over a mile but I’mll win over a hundred. Beat me over a hundred and I’mll endure for a thousand. I’mll cycle round the fucking planet if I need to. I made it a private point of principle on expeditions to never be the first to give up. To never admit defeat, exhaustion or weakness before anyone else. It was a ridiculous and irritating trait when we should have been enjoying the bond of hardship. I made myself harder than anyone I ever walked or rode alongside. (I am sure a few equally fragile egos among my friends will dispute this!)

Being fit is easy. It’s being hard that is hard.

I used to love that saying.

I wanted to prove myself all the time. Cold showers. Run till you puke. In winter I enjoyed opening the car windows wide, challenging myself how long I could tolerate the icy wind. Music blasting in the fast lane, joyful at finding something that made me different, something I was good at.

But now, heater on, windows up, driving extra slow to delay getting home, crying at the radio, I accepted the truth. I was not hard. I was fragile.

Throughout these years, guilt sharpened the good and poignant moments. Watching my children in running races, Nativity plays, birthday candles: everything tore me open and brought me to tears. My life reduced to sobbing in the slow lane. I did not want to be alive anymore. I needed help.

“Talk to me,” said the doctor. “Tell me how you feel.”

I crumpled.

No, I was not struggling financially. Yes, all of my family was healthy. No, nobody had died. Yes, you’ve got that right, my career basically does involve me going on holidays and goofing around on the internet. My life would be the envy of billions. I could not hold the doctor’s eye.

What then was the matter? It was this. After so long living a life of personal purpose and direction, I objected to the constraints that came with becoming a father more than I revelled in the wonders. I was not proud of that. Next year I would turn forty. That landmark loomed large and heavy upon my mind. Forty! Bloody hell. It was time to change. The shadow of middle age had engulfed me. Middle age. Half way. Midsummer. This was my midsummer morning.

Counselling helped me gain perspective. I looked forward to the sessions. They were irritatingly, amusingly combative. I knew what answers Molly was angling for. I knew they made sense. But I wriggled and argued with all my might. I didn’t want to concede. Back in the sixth form a teacher once said that all I would be good for in life was to be a politician. It was not a compliment. I was just good at arguing. When Laurie Lee left school his teacher had declared, “off you go and I’mm glad to get rid of you.”

Patiently, persistently, Molly wore me down, logically and calmly dismantling my fiery emotion. She showed me what I already knew.

All of this was my choice. Every single thing. I chose to get married and become a father. Nothing would change those choices. I did not want to. I chose not to walk away from them. This was my life. My responsibility. There was nobody to blame and, even if there was, blame would not help. The choices were mine. It was up to me alone what I made of my life from now on.

Slowly I began removing the wedge I had hammered between Sarah and me. It had been battered in by years of stubborn fury, but I began to work it free, remembering why I loved her and trying to become kind once again. I married Sarah because she was lively, funny, sparkling, and added so much to who I was. I wanted to see all those things once again, rather than just a target for my grudges.

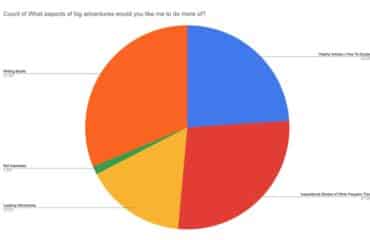

I began to turn closer to home looking for adventure. Searching for opportunities rather than groaning at the limitations in my life. I found short, local escapes that were compatible with real life. I called them microadventures. A little adventure is much better than no adventure. They restored my sanity, providing a dose of wilderness, offline stillness, simplicity, and physical toil. The idea spread to others. It seemed there were many in similar positions, dreaming of adventure but struggling to make it happen. Hearing about other people getting out on adventures of their own made me feel better still.

Fast forward a while and the nappy years were now behind us. The sniping and exhausted bickering was fading. Clouds were lifting and the skies brightening. Our children old enough to be mostly reasonable, good company, low maintenance. Sarah and I began to get some of our individual lives back, her with her career and me via microadventures.

Even the glimmering prospect of a bigger trip became possible once again, without putting too much of an unfair burden on the family. I knew I could not have Laurie’s eternal summer any longer. Those days were past and I at last accepted that. But, perhaps, I could get one last taste. A month away, by myself, was unwarranted in terms of our domestic childcare balance sheet. It would place yet more of a burden on Sarah. But we could make arrangements to make it workable. My children would miss me when I was away, and I would miss them. But, in my own muddled and inelegant way, I wanted to do this for them. I had not been a particularly good father so far. I certainly was not setting an example I was proud of at home. But I wanted, more than anything else, to be a good dad.

I wanted my children to realise that there are many possible paths in life, like the mesh of animal tracks fanning out from a waterhole. They did not have to follow the same crowded route that everyone else was taking, the one prescribed by school and society. If they did pick that path then I at least wanted it to be a deliberate decision. I hoped to fill them with love for the natural world and wilderness, and to teach them to be curious, weird, wild, and bold. Above all, I want them to seize their lives and opportunities. Please don’t just settle! Don’t be boring!

But I needed to show them this way of life, not just preach about it. It was time to get back to living like this myself.

Above my desk, this quote from Jung. I see it every day.

“The life that I could still live, I should live, and the thoughts that I could still think, I should think.”

I bought a violin.

[This is an extract from my book My Midsummer Morning]

I needed this. Thanks for the exposed self examination and articulating the pain that can comes from our own evolution.