[Here’s a link to other forays around my map.]

“I am struck by the fact that no work has been shirked when a piece of cloth is produced, every thread has been counted in the finest web… The operator has succeeded only by patience, perseverance, and fidelity…” – Thoreau

“We too have our thaws. They come to our January moods, when our ice cracks, and our sluices break loose. Thought that was frozen up under stern experience gushes forth in feeling and expression. This is a freshet which carries away dams of accumulated ice. Our thoughts hide unexpressed, like the buds under their downy or resinous scales; they would hardly keep a partridge from starving. If you would know what are my winter thoughts look for them in the partridge’s crop.” – Thoreau

There are two types of people in the world. Those who love snow and those who do not. There is no such thing as a child who does not like snow. A few people have valid objections to snow: broken hips and confounded commutes, for example. But anyone else whose heart does not leap a little at the first falling snowflakes is a miserable curmudgeon! I genuinely feel that I get as excited today as I did back on those glorious occasions at school when someone in the classroom yelled, “it’s snowing!” and happy pandemonium broke out.

The south of England being a mild sort of place, the best I can hope for each year is a couple of days of jolly disruption, a couple of sledging outings, and a covering of a couple of inches. After four consecutive rainy outings I was excited to get out this morning, not least of all because I have noticed the dawn arriving a little earlier recently. The seasons are on the move.

“As the days lengthen, the cold strengthens.” It’s an old proverb that certainly has some scientific truth. The Northern Hemisphere receives its least direct sunlight on the winter solstice, but in many places the coldest average temperatures of winter aren’t until later. This delay in the arrival of our coldest temperatures is better known as seasonal lag. It happens because the amount of solar energy arriving at the ground is less than the amount leaving the earth for a few more weeks.

Oceans and bodies of water — which take longer than land to heat up and cool down — keep temperatures from rising very fast. Not until the Northern Hemisphere sees a net gain in solar energy (more heat coming in than going out) do average temperatures begin their ascent. The exact timing of the coldest stretch of the year depends on several factors, including how close you live to water, prevailing wind direction and the amount of snow cover (snow is great at reflecting the sun’s heat straight back into space).

I had parked my car, donned my wellies, and turned to begin my walk when an elderly gentleman hurried out of the garden gate under an arched beech hedge demanding, “who are you?” He was unhappy that I had parked on the open empty ground opposite his home. I was causing no disturbance but the man was adamant that it was “private, so you can’t park here.”

I was polite, if non-plussed, and returned to my car. The man stood and watched me move in his country check shirt. It was a cold morning so he had obviously bustled out from his breakfast and Daily Telegraph crossword to shoo me away. An inconsequential incident (I parked 200m down the track and carried on with my day), but it set the tone for what is becoming a recurring inkling on these explorations: most places I go I feel either excluded, unwelcome, or only grudgingly tolerated. Although I saw only one other person across the grid square, almost every turn I took was marked with signs cautioning me to Keep Out of every direction except for the hair thin slice of permitted footpath I was on. And signs expressly forbid me from entering the wood that I had especially looked forward to visiting –a few hundred square metres of deciduous trees, with two streams converging in it.

But enough of this moaning: it’s snowing, for heaven’s sake! This is a day for jubilation surely. Even the thinnest blanket of snow muffles the world and makes the day quieter. I heard a buzzard and the cawing of rooks, but even the omnipresent motorway police sirens were quieter today. A pair of squabbling goldfinches zipped in and out of the hawthorn hedge, scolding each other. The goldfinch is one of my favourite birds, and ever since I hung niger and sunflower seeds outside my shed they have been regular, noisy, colourful, welcome visitors. (There’s a charming line in the book Leonard and Hungry Paul about a mother who looked ‘after everyone in her life as though they were her garden birds: that is to say, with unconditional pleasure and generosity.’)

The goldfinch is a highly coloured finch with a bright red face and yellow wing patch. Sociable, often breeding in loose colonies, they have a delightful liquid twittering song and call. Their long fine beaks allow them to extract otherwise inaccessible seeds from thistles and teasels.

In Great Britain during the 19th century, many thousands of European goldfinches were trapped each year to be sold as cage birds. Because of the thistle seeds it eats, in Christian symbolism the European goldfinch is associated with Christ’s Passion and his crown of thorns. The European goldfinch, appearing in pictures of the Madonna and Christ child, represents the foreknowledge Jesus and Mary had of the Crucifixion.

In the poem The Great Hunger by Patrick Kavanagh, the European goldfinch is one of the rare glimpses of beauty in the life of an elderly Irish farmer:

The goldfinches on the railway paling were worth looking at –

A man might imagine then

Himself in Brazil and these birds the birds of paradise

And the Amazon and the romance traced on the school map lived again.

Donna Tartt’s novel The Goldfinch won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. A turning point in the plot occurs when the narrator, Theo, sees his mother’s favourite painting, Carel Fabritius’s The Goldfinch, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Fabritius died aged 32, caught in the explosion of the Delft gunpowder magazine on October 12, 1654, which killed at least 100 people and destroyed a quarter of the city, including his studio and many of his paintings. Few of his works are known to have survived. The Goldfinch was painted in the year Fabritius died.

Tree branches in winter stand out like the veins and vessels of a vascular system, silhouetted against the low sunlight and framed by a colossal black snow front moving my way. I love watching weather approach. The sky nearby was hazy, as though covered with gauze, and any moment now the falling snow would reach me.

Being a big kid, I was hoping for those giant, soft snowflakes that fill the sky and cover the earth. I also, of course, love the individual magical 6-pointed kind of snow.

Hardly any scientific finding has permeated popular culture more profoundly, transmuted its truth into a more pervasive cliché, or inspired more uninspired college application essays than the fact that no two snowflakes are alike. But for the vast majority of human history, the uniqueness of snowflakes was far from an established fact.

In the early seventeenth century, while revolutionizing science with the celestial mechanics of the macro scale that would land his mother in a witchcraft trial, Johannes Kepler turned his inquisitive imagination to the micro scale with a rather unusual Christmas present he made for a friend — a booklet titled The Six-Cornered Snowflake, exploring in a playful and poetic way the science of why snowflakes have six sides. When one landed on his sleeve in the bitter Prague winter, Kepler found himself wondering why snowflakes “always come down with six corners and with six radii tufted like feathers” — and not, say, with five or seven. Centuries before the advent of crystallography, the visionary astronomer became the first to invite science into this ancient dwelling place of beauty and to ask, essentially, why snowflakes are the way they are. But it would be another two centuries before this intersection of science and splendor enraptures the popular imagination with the nexus of truth and beauty in the form of ice crystals — a task that would fall on a teenage farm-boy in Vermont.

On January 15, 1880, Wilson Bentley took his first photograph of a snowflake. Mesmerized by the beauty of the result, he transported his equipment to the unheated wooden shed behind the farmhouse and began recording his work in two separate sets of notebooks — one filled with sketches and dedicated to refining his artistic photomicroscopy; the other filled with weather data, carefully monitoring the conditions under which various snowflakes were captured.

For forty-six winters to come, this slender quiet boy, enchanted by the wonders of nature and attentive to its minutest manifestations, would hold his breath over the microscope-camera station and take more than 5,000 photographs of snow crystals — each a vanishing masterpiece with the delicacy of a flower and the mathematical precision of a honeycomb, a ghost of perfection melting onto the glass plate within seconds, a sublime metaphor for the ecstasy and impermanence of beauty, of life itself.

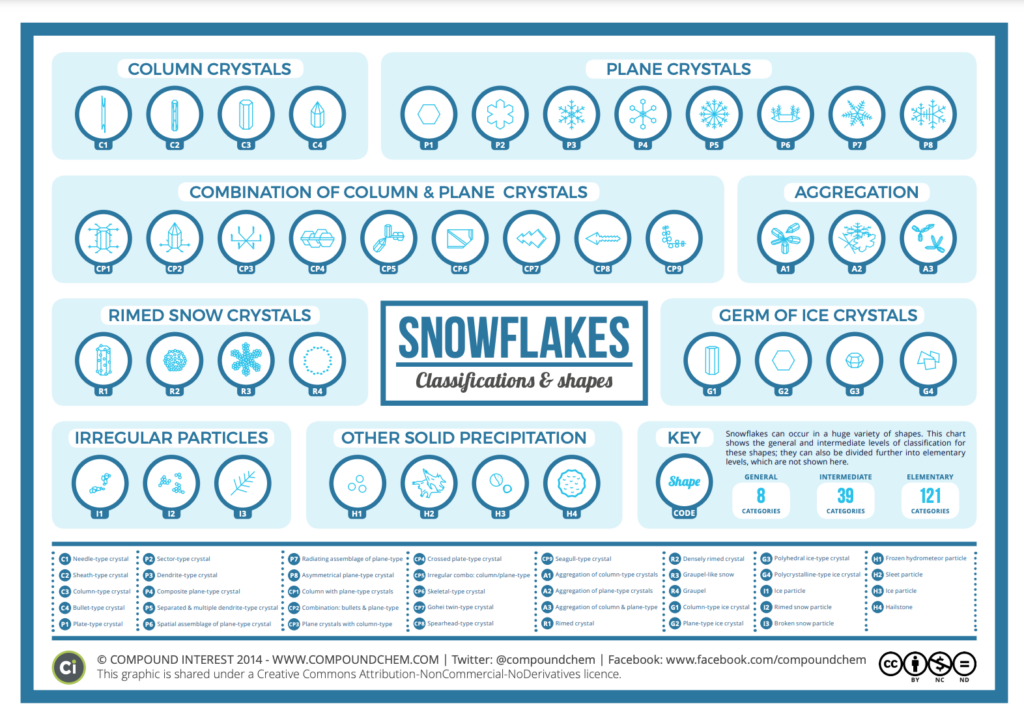

Instead of this beauty, however, the ground was soon covered in what looked like beanbag pellets. And I learned a new word. ‘Graupel‘ are soft, small pellets formed when supercooled water droplets (at a temperature below zero) freeze onto a snow crystal, a process called riming. If the riming is particularly intense, the rimed snow crystal can grow to an appreciable size, but remain less than 0.2 inches. Graupel is also called snow pellets or soft hail, as the graupel particles are particularly fragile and generally disintegrate when handled.

The dusting of snow hampered my hopes of channelling my inner Tristan Gooley, tracking the footprints of ants through the snow, seeing signs of life wherever I looked. Instead I was limited to noticing the tracks of a pickup, the swish of a sledge, the gait of a runner, the hop of a rabbit, the strut of a pheasant, and the heroic effort of a mole, hauling its way through the dark frozen soil beneath us.

The mole is the only mammal to live solely underground and they achieve this because they have a greater proportion of red blood cells than other mammals. This helps them to live in an environment where oxygen levels are low, typically 7%.

They are phenomenal diggers and can shift 540 times their own body weight of earth and tunnel up to 200 metres per day. Since they are rarely more than 150mm in length, weighing in at between 110-120 grams, this is one mean feat. Moles are industrious hard workers. Typically they work in patterns of 4-hour shift cycles. This means 4 hours working, 4 hours sleeping; all day every day.

There is a common misconception that moles are blind. They are not. They are light sensitive. Their ears are situated internally behind their shoulders, so mole’s snout acts rather like a sound tube. Sensory hairs strategically placed on their body also help mole to navigate in the darkness. Moles eat worms, grubs and larvae. They need to eat around 20 worms per day, or half their body weight in order to survive. If they cannot collect that quota from their current run system, they will carry on digging new runs and hence continue to throw up new mole hills above them.

People in the late eighteenth-century believed that if you held a mole in your hand until it died, your hand would acquire healing power. Until the twentieth-century, it was believed that the blood of a freshly killed mole, dripped onto warts, would cure them. In the twentieth-century, as recently as 1971, mole’s hands and feet were still carried in bags, around the neck as remedies in the Fens in Cambridgeshire. They were believed to protect against toothache epilepsy and rheumatism amongst other illnesses and ailments.

Oddly, perhaps, I found these facts of this charming creature on the British Mole catchers Website. The idea of a professional who specialises in mole control can seem like a quaint relic from the past. In the 18th century mole-catchers were employed by every parish in England to keep the mole population under control. Catching these creatures required such skill that practitioners were remunerated more generously than surgeons. Mole-catchers zealously guarded their methods, divulging them only to their own children.

Mole control became a national policy in 1566, when a bitter cold period known as the Little Ice Age threatened England’s food supply. Queen Elizabeth passed “An Acte for the Preservation of Grayne”, which would remain in force for the next three centuries. The law prescribed bounties to be paid for the destruction of a long and dubious list of agricultural vermin, including everything from hedgehogs to kingfishers. Some parishes paid out a half-penny per mole, others appointed mole-catchers with contracts lasting up to 21 years. In addition to their salaries, mole-catchers sold the silky mole skins, which were prized for the tailoring of waistcoats.

Trudging through the white fields felt like taking a trip back in time. A village church in the distance. Black rooks cawing and swirling through the snow-filled white sky. Partridges flying with a whirr of short, fast wings. A woodcock (or perhaps a snipe?) bursting from cover. There is less to see, but different things to feel. I imagined myself as peasant farmer on this huge landowner’s estate, struggling to make ends meet, and cursing the snow. I gave thanks for my expensive winter clothing and made sure to savour my flask of soup, particularly as today I enjoyed the novelty of having my own home-baked bread to accompany it. This loaf was so easy to make, cost pennies, looked so pretty, and tasted so blooming good (I scoffed almost half of it in one sitting). Baking bread is an activity to celebrate and encourage. Toast it, slather it in almond butter, tear off chunks and eat them warm, or gift a loaf to your neighbour or postman… (Here are two to kick you off: very fast focaccia, very easy but overnight white loaf.)

It is a fortuitous quirk that such a basic, cheap, nutritious food is also delicious. This probably accounts for its longevity in diets across the world. Bread was central to the formation of early human societies. From the Fertile Crescent, where wheat was domesticated, cultivation spread north and west, to Europe and North Africa, and east towards East Asia. This in turn led to the formation of towns, as opposed to the nomadic lifestyle, and gave rise to more and more sophisticated forms of societal organization. Charred crumbs of a flatbread made by Natufian hunter-gatherers from wild wheat, wild barley and plant roots between 14,600 and 11,600 years ago have been found at the archaeological site of Shubayqa 1 in the Black Desert in Jordan, predating the earliest known making of bread from cultivated wheat by thousands of years. In the Deipnosophistae, the author Athenaeus (c.A.D.170 – c. 230) describes some of the bread, cakes, and pastries available in the Classical world. Among the breads mentioned are griddle cakes, honey-and-oil bread, mushroom-shaped loaves covered in poppy seeds, and the military specialty of rolls baked on a spit.

As if my smugness at eating my own bread in a snowy field needed any boosting, let me tell you that I was warm and comfortable too, thanks to my scarf which I knitted myself. Have I mentioned my scarf yet? Rest assured, if you have been within earshot of me in the past month, then I will have mentioned my scarf! What strange twists the world has taken for me to find myself with sufficient time on my hands to Google “how to knit a scarf“… Suffice to say, it has been very satisfying to turn 350 metres of wool into one long and wonky scarf. And let us leave it there for today before I dive down the Google rabbit hole of “the history of knitting”! Leave me on the crunchy frozen footpaths around the winter wheat fields at the foot of a long ridge of hills, amongst a billion falling flakes of snow, very happily eating my own bread and catching snowflakes on my gloves. Will I bag all eight categories of snow, I wonder? Column crystals, Plane crystals, a Combination of column & plane crystals, Aggregation of snow crystals, Rimed snow crystals, Germs of ice crystals, Irregular snow particles, and Other solid precipitation…

Great article thank you I read all about snowflakes in professor Brian cox book the fact that blew my socks off was it’s 4 dimensional! You can read its life story in its shape! Also the lovely professor Alice Roberts book tamed traces the history of stuff like wheat it tamed us not the other way round