[Here’s a link to other forays around my map.]

I passed a primary school, delighted to hear the shrieks and playground laughter after the isolation of lockdown homeschooling. I read three colourful quotes displayed outside the school.

- “Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.” – Carl Sagan

- “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” – W.B. Yeats

- “The more you read, the more things that you will know. The more you learn, the more places you’ll go.” – Dr Seuss (who, incidentally was not a Doctor at all, but added it to his pen-name to appease his father who had wanted him to study medicine.)

I liked these: perfect for an education based on curiosity not box ticking. But also a good summary of what excites me about diving deeply into random grid squares across my not-very-exciting suburban map. The sheer abundance of every inch is, once again, my chief surprise.

I didn’t feel as upbeat as this when I began for the day. The benefit of a few metres of elevation was being afforded a fine view, on a beautiful spring morning, across to the flat marshes and creeks of one of my previous grid squares. But right here in front of me was the poverty of a forgotten-looking housing estate. I didn’t feel comfortable taking photographs here. The diversity of living experiences across the 20 kilometres of my map has been interesting. There are so many different worlds within a few miles of where I live, and I don’t particularly belong in any of them. At various times I have worried about being shooed-away by hoity, indignant posh people in Range Rovers, by close-cropped Travellers in pick-up trucks, by farmers in tractors and –today– by haggard young mums with prams and extra large cans of Monster. Around the estate’s concrete blocks of flats I saw kids bunking school, people in dressing gowns smoking a wake-up cigarette in the sunshine, peeling paint and disrepair. Yet just a couple of hundred metres away I would find peaceful cul de sacs with cherry blossom trees, trim gardens and all the commuters already up and gone to work. The diversity of landscapes meandering around my map is fun; the disparity of lifestyles is often harsh and unkind.

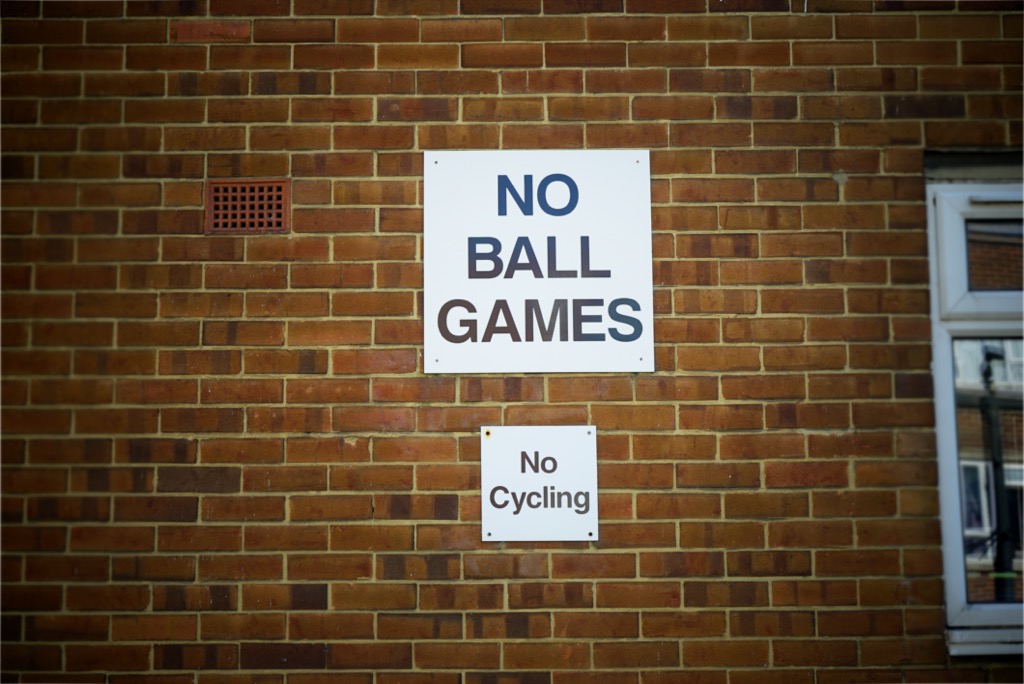

When this estate was built in the housing crisis after the second World War, it was officially opened by Prime Minister Clement Attlee. He declared, ‘We want people to have places they will love; places in which they will be happy and where they will form a community and have a social life and a civic life.’ I know nothing from walking around for an hour, listening to accents from across the globe. But I noticed that the community library was ‘temporarily closed until further notice’ due to the pandemic and that every patch of grass bore signs warning ‘No Ball Games. No Cycling.’ But on the plus side there was a community gym with an outdoors weights area, a youth club with a football cage and the cafe on the parade of shops was busy with old folk enjoying the sunshine and each other’s company as the lockdown restrictions gradually ease.

On one of the grass verges (where fun was forbidden), I noticed small mauve pink flowers growing amongst the bright yellow dandelions and curls of dog shit. The Seek app on my phone told me that they were Musk Stork’s Bill. What a name! What a delight! It was just an obscure little flower on a scrappy mown verge, but the name elevated it to glory and made me smile. And the kids in the school playground were still hollering and laughing. It’s hard not to be optimistic for the world when children are around. I smiled and set off to see what else today’s grid square might reveal.

Across the road from the housing estate I found myself riding up and down long, straight Victorian terraces, brick-built with four tall chimneys on each building from the days of coal fires. Those polluting fires are long gone now, of course. Take away too the parked cars that hem the streets in on both sides and these streets can become a lovely area for outdoor living, with kids playing ball games and cycling in the streets, and all the sense of community that Clement Attlee was hoping for. I’m optimistic about the future here this morning.

I cycled past a road sweeper van (named in the Meaning of Liff as a ‘Vancouver’), bumped over a series of sleeping policemen (what a wonderful term that is), and slowed to allow a blind man cross at a zebra crossing (ditto). He continued on his way, feeling along the pavement edge with his white stick. Both of us concentrating on paying attention, noticing, making the invisible visible. Different ways of exploring, noticing. James Biggs of Bristol claimed to have invented the white cane in 1921. After an accident claimed his sight, the artist had to readjust to his environment. Feeling threatened by increased motor vehicle traffic around his home, Biggs decided to paint his walking stick white to make himself more visible to motorists. It was not until ten years later that the white cane established its presence in society. In February, 1931, Guilly d’Herbemont launched a scheme for a national white stick movement for blind people in France. The campaign was reported in British newspapers leading to a similar scheme being sponsored by rotary clubs throughout the United Kingdom.

I love April. It has taken two years of locked down springtimes for me to realise that. I think I previously would have ranked April as a cold and blustery month, but the heightened localness and lack of distraction during lockdown means I have paid attention to how the natural world bursts back into life in April. Robert Browning pinned that down long before me.

I walked around a leafy graveyard, accompanied by the loud songs of chaffinches, robins and blackbirds. The grass was a fabulous mosaic of dandelions and daisies. The temptation for many of us in lockdown Britain is to get on with jobs in the garden – including getting that lawn into the classic British stripe. But results released by Plantlife demonstrate the spectacular benefits both we and our garden wildlife receive from not mowing for a month. Like the nation’s haircuts, can we adapt to a less rigorous regime and ‘No Mow May’? Over 200 species were found flowering on lawns including rarities such as meadow saxifrage, knotted clover and eyebright. The top three most abundant lawn flowers are daisy, white clover and selfheal. Over half a million flowers have been counted, including 191,200 daisies. The highest production of flowers and nectar is on lawns cut every four weeks, whilst longer, unmown grass had a wider range of flowers.

There are three aspects to the official name and common names of common dandelion, Taraxacum officinale. Officinale, the species name, is a Latin term that is attached to those herbs that contain long-accepted medicinal properties.

The second part of the origin of the scientific name comes from the appearance of the leaves of the plant. Consensus is that they resemble the canine teeth of a lion. Dents de lion is French for teeth of the lion. The French also called this plant ‘pis-en-lit.’ Dandelions are known diuretics. A diuretic is something that removes fluid from your body. Let’s just say that eating dandelions before bed could cause you to pis-en-lit or wet the bed. The most poetic name for dandelions may be the Chinese name which translates to, “flower that grows in public spaces by the riverside.”

The first known written record of dandelions being used medicinally dates back to the 10th and 11th Centuries. But, it’s recorded use is believed to date back to Ancient Rome and the Anglo Saxons. It first appeared in European history in the 13th Century when it was used by the Welsh. Dandelions were also used to make dye – pale yellow from the sunny yellow blossoms and a purplish tint from the inner ribs of the leaves. Even today, many gardeners use the plants to make nutritious tea and flavourful wine.

The name “daisy” is considered a corruption of “day’s eye”, because the whole head closes at night and opens in the morning. Chaucer called it “eye of the day”.

Of all the floures in the mede,

Than love I most these floures white and rede,

Soch that men callen daisies in our town;

To hem I have so great affection,

As I said erst, when comen is the May, 5

That in my bedde there daweth me no day

That I nam [I am not] up and walking in the mede,

To seene this flour ayenst the Sunne sprede,

Whan it up riseth early by the morrow.

That blissful sight softeneth all my sorrow.

Whilst the inventor of the steam locomotive rests here in a pauper’s grave, one of his work colleagues amassed enough money for a large family tomb. According to the inscription, his wife ‘died in the peaceful assurance of everlasting life, her sorrowing children gratefully record in their affectionate remembrance the many domestic and private excellencies which adorned her character.’ I wonder what my own grave may say one day?

Amongst the 500 years of gravestones were three Protestant martyrs, burned at the cross. Such religious fervour is hard to imagine in Britain these days. We are far more diverse and tolerant these days. I wonder what those angry folk would have made of some of the other churches I came across within this single square kilometre. A Methodist chapel converted into a Vietnamese Buddhist Meditation Centre; The King of Glory Assembly; an old cinema converted into a church for the Evangelical Alliance and Assemblies of God UK; and a red corrugated iron warehouse on an industrial estate that was home to The Redeemed Christian Church of God.

Crossing over the railway line I was struck by how green the embankments were. They add up to thousands of miles of wild land and be important corridors for nature. Railway tunnels, cuttings and bridges offer many habitats for animals and plants to thrive in. Network Rail says, ‘We work closely with national and local organisations to make sure we meet, and where possible exceed, the legal requirements when it comes to protecting species and enhancing their environment. Our project work can have an immediate impact on local biodiversity, but we’re testing methods of giving back to the natural environment more than our work has taken – often known as a net positive approach.’

I dropped down from the residential streets into the town centre, into a hotchpotch of old buildings and winding ancient lanes mixed up with modern ‘improvements’ – shopping centres, roundabouts and one way systems. There was a 9th Century church down by the river. There were also discarded vodka bottles with Eastern European labels, plenty of McDonalds’ rubbish, and, mysteriously, a neat triangle of a tin of chickpeas, new potatoes and tomato sauce left on the riverbank. There were two nice benches to relax on by the water, but also a third bench upended into the river. A tall elm tree shaded the benches with its branches of bright green new spring growth. I didn’t recognise it as an elm tree, as featured in Browning’s poem mentioned earlier, because they are sadly rare these days due to Dutch Elm disease. This now infamous tree disease has killed millions of elm trees in the UK over the last 40 years. It’s changed parts of our landscape forever and it’s still spreading north. Dutch elm disease is caused by the fungus Ophiostoma novo-ulmi which is spread by the elm bark beetle. It got its name from the team of Dutch pathologists who carried out research on the diseases in the 1920s.

Elm bark beetles breed in the bark of cut, diseased or otherwise weakened elm trees then disperse to healthy elm trees where they feed. As they feed, the spores of O. novo-ulmi are introduced into the xylem (channels for water and nutrients) of the healthy tree, releasing toxins and causing the vessels to block and the tree to wilt and die. Since its introduction to the UK, it has killed millions of our elm trees. It has devastated populations in mainland Europe and North America too. Dutch elm disease was accidentally imported into the UK from Canada in the late 1960s. It spread quickly, reaching Scotland in just 10 years.

An information sign told me that this area in the centre of town was a fashionable area to live until the 17th Century. There have been phases of beer houses, water mills, clay pipe makers, and greengrocers, all built on top of the original Roman road through the town. Today there is an assortment of small shops, celebrating all manner of people from every corner of the world. At times on my map I have felt the freedom of wilder and quieter landscapes. Today though I enjoyed the bustling pleasure of times spent exploring marketplaces in Africa and Asia, as well as the worldwide pleasure of people watching. The shops I strolled past included Transylvania Groceries, Glam Beauty Lounge, Property king Estate Agents, ‘Continental Foods – African, Caribbean, Filipino, Indian, Nepalese, Thai, Sri Lankan, Vietnamese’, an Efes Turkish restaurant, ‘Eko food – African foods and ready meals’, Lucky Nails, ‘All Day Cafe: sandwich panini roll fresh salad late orange juice’, a slot machine casino and the local branch of Cash Converters.

The menu of one café was resolutely old-school English, while, next door’s café offered a ‘Healthy Breakfast’ of Eggs Florentine for £5.90 or ‘Mashed avocado, double poached egg, grilled tomatoes, halloumi and 2 toasting muffins’ for £6.20.

- Egg, bacon and sausage: £3.20

- Egg, bacon and mushrooms: £3.20

- Egg, bacon and bubble: £3.20

- Egg, bacon and beans: £3.20

- Egg, bacon and tin tomatoes [sic]: £3.20

- Egg, bacon and black pudding: £3.20

- Egg, bacon and onion rings: £3.90

The price hoik for onion rings intrigued me…

My diligent meanderings were interrupted close to a pub where Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants’ Revolt, ‘quenched his thirst with flagons of ale’ en route to meeting the King and then getting decapitated for his demands and his insolence. What caught my eye was a table outside a church covered in a pink polka dot cloth, bunches of flowers and stands of cakes. I have not been to a café for so many months so it felt quite the treat to drink coffee and eat a scone in the sunshine outside the church (clotted cream is fully vegan, right…?). The old dilemma of jam first or cream first reared its head. When it comes to baked goods, few issues carry the contentions of the great scone debate: should the cream or the jam be spread first? Cream tea has been served in the UK since the 11th century and arguments surrounding the order of spreading the scone’s traditional toppings have ruminated ever since. While those in Devon typically spread the clotted cream first followed by jam, the Cornish tradition is to spread jam first followed by cream. Finally, we have some clarity on the issue, as it’s revealed how the Queen takes her scones. An exemplar of British traditions, the Queen reportedly prefers jam first.

An elderly lady watched me going through the rigmarole of taking a photograph of my scone before scoffing it. Fortunately I really enjoy taking pictures so it never feels like a palaver to me. “Are you a photographer, or are you learning?” she asked. “I think you’re always a learner, aren’t you?” I replied, smiling.

It was market day today and the High Street was busy with trading stalls and pedestrians browsing amongst the racks of clothes, household goods, vaping supplies and vegetable stalls. Bunting fluttered overhead in the breeze, the whole street criss-crossed with red and white St George cross flags. It was St George’s Day this week and I liked seeing these flags on display, despite England’s general reluctance to celebrate its national saint’s day. St George is also the patron saint of Venice, Genoa, Portugal, Ethiopia, Georgia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Catalonia among others.

I pedalled quickly past the boring, bland modern shopping centre with all its outlet stores and the revolting waft of Subway. Subway has a one-of-a-kind smell. It’s that sweet, herby, bready scent that wafts in such pungent clouds that you don’t even need to go inside a store to smell it. Just walking past a Subway is enough. You’ll be strolling down a footpath when suddenly you’ll find yourself feeling disgusted or hungry, depending on how you feel about Subway. More interesting to me was the industrial estate I headed for. I love places like this, with businesses run out of warehouses and all sorts of banging machines, weird looking equipment, and men in overalls. I think part of my fascination comes from feeling out of my depth in places like this. I’ve never had a job that involves whacking things. I barely know which way to hold a hammer. And whenever I need to venture into these sort of workshops or garages, perhaps to get a car fixed, I feel wimpishly emasculated, clueless and ripe for being ripped off! So I liked just cycling around the units, peering in curiously, on my way to look at the creek behind the gasometer. Gas holders helped warm the UK’s homes for decades. But now they are being removed, with the National Grid saying land is being “redeveloped and given back to communities”.

In the 200 years that the UK has been using gas power, the country has got used to the distinctive sight of “gasometers”. These gas holders have stored coal gas (town gas) and later natural gas for the UK’s urban areas, but now all but a handful are obsolete. After natural gas was discovered in the North Sea in 1965 the UK gas network went through a massive process of conversion. Town gas stopped being used and North Sea gas started to be transported into the UK under high pressure in pipes.

From then on, it was only when extra capacity was needed in the gas network that gas holders would be used. As the network of pipelines became larger and more effective, these occasions became fewer. Our skylines are littered with their massive metal frames. The National Grid owns over 500 gas holders. And there are others owned by other companies. Though they are now defunct, it’s undeniable that they continue to play a part in British culture. Perhaps the most famous British gas holder looks over the Oval cricket ground. Like the pigeons that perch on it, it’s been a subject of Test Match Special presenter Henry Blofeld’s ramblings for decades. For artists they have a dystopian edge. Raves spring up and are closed down around them and in the 1997 film Shooting Fish the protagonists, perhaps unrealistically, tried to live in one.

“The UK has been using gas for the past 200 years,” says Keith Johnson, a land regeneration manager working for National Grid. “Gas used to be made from burning coal. Coal would be brought to an incinerator near one of the holders via train or boat,” he explains. “As the gas was pumped into the holders, the domed container would rise, telescoping up in enormous metal sections, guided by its steel framework.”

And so, the cylinders would rise. Slowly led from the ground by wheels tracing upright girders, the gas holder would fill up.

Gas holders are also known as gasometers, a term coined by the inventor of gas lighting, William Murdoch. To the disgruntlement of his contemporaries, who complained that this so-called gasometer was not a meter but a container, the name gasometers stuck and slid into general use. To avoid confusion, the structures are now most commonly referred to as gas holders, though gasometer is still accepted.

Behind the gasometer and the industrial units the stream that ran through the centre of town, past the ford where hermits helped travellers cross in olden times, it morphed unnoticed from a small stream into a marshland creek, heading towards the tidal marshes I explored some months ago. This had turned out to be a fascinating grid square to explore. Beginning with the run-down estate, then down through the thousands of years and layers of a town centre, out to the margins of welding businesses and the beginnings of tidal marshlands, and finally past the site of the old paper mill which is now a ‘a luxury collection of apartments within a thriving waterfront urban village, ideal for families and couples wanting to live in a leafy garden suburb setting within easy commuting distance of the capital, where aspirations are brought to life’ and back up the hill to the less-aspirational estate hoping, really, to cope and make do, with spiked railings round every flat roof and a community network of trained volunteers and expert support helping families with young children through their challenging times.

Comments