[Here’s a link to other forays around my map.]

First stop: the skate park. As it was a school morning I had the place to myself so I amused myself riding the ramps on my Brompton for a little while. I didn’t dare tackle the steepest ramp though, and certainly wouldn’t have done so on a skateboard! The history of skateboarding dates back to the 17th-century when roller skates were created as a summer alternative to ice skating. And now Skateboarding is one of the five new sports to be introduced in the Olympic program in Tokyo. There are various theories about the origins of skateboarding, but it is generally held that the sport began in the 1940s on the west coast of the USA when metal wheels were attached to a narrow wooden board. In the 1950s, clay composite replaced metal as the material of choice for the wheels, and the first ‘Sidewalk Surfboard’ became commercially available, which in turn developed into the skateboard that we know today. The sport was a big hit with the younger generation and with the advent of the urethane wheel in the 1970s, grew in global popularity. Since the 1980s, skateboarding has been an essential part of street culture. In skateboarding, the rider is free to select which parts of the course to tackle and which tricks to perform. Even when the same tricks are performed, the flow of the performance can depend greatly on the speed attained. While speed is an important element, marks are awarded for the overall level of difficulty and originality. In addition, competition judges also take into account the overall flow, timing, consistency and the extent skateboarders are able to create the sensation of being suspended in mid-air.

How did I know that the skate park was usually frequented by school kids? Not because of all the fizzy drink cans strewn around the ground vaguely near the provided bins. No, it was the sight of one of those yellow and black pencils only seen in schools that tipped me off. It’s weird how I remember their name (Staedtler Noris), their smell, the taste when you crunched the end, yet can recall very little of use I ever wrote with one! With his ambition of selling pencils worldwide, Johann Sebastian Staedtler laid the foundation back in 1835 for what is now the STAEDTLER Group. In 1853, the pencil maker from Nuremberg showcased his wares at the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York; just a few years later, these high-quality, German-made products had already made a name for themselves in France, Britain, Italy, Russia, America and the Middle East. For Johann Sebastian Staedtler, a fascination for pencils ran in the family: his ancestor, Friedrich Staedtler, worked as a ‘pencil-making craftsman’. In 1662, Friedrich Staedtler was mentioned for the first time in the official records of Nuremberg as a “lead pencil maker” – and his descendants are continuing the family tradition.

The roadside verges grow thicker and more green every week that I’m out exploring. I stopped today to nibble a few leaves of garlic mustard, also known as Jack-by-the-hedge. The leaves of Garlic mustard are regularly used in salads, or as a flavouring for fish or meat. Young, fresh leaves can be picked in September when they first appear, and may be harvested until the flowers bloom the following spring. Garlic mustard has been used as an antiseptic herb for treating leg ulcers, bruises and sores, coughs and colds, clearing a stuffy head, to encourage sweating and even as a cure for colic and kidney stones. In Somerset, the fresh green leaves were rubbed on feet to relieve cramp.

And yet the plant, which I look on fondly as a nice nibble and a regular feature of British springtime has become a very troublesome invasive plant across the Northeast, Midwest and Northwest of the United States. The plant was introduced to North America in the mid 1800s for its herbal and medicinal qualities and as erosion control. Garlic mustard is a threat to the biodiversity of many native ecosystems.

This plant spreads its seeds in the wind and gains a foothold in fields and forests by emerging earlier in spring than many native plants. By the time native species are ready to grow, garlic mustard has blocked their sunlight and outcompeted them for moisture and vital nutrients. This advantage is only strengthened as climate change continues to alter seasons faster than native plants can adapt. Invasive species that crowd out forest ecosystems inhibit trees, which store large amounts of carbon dioxide, from growing.

Because the understory of a forest is so important for insects and other species at the bottom of the food chain, invaders like garlic mustard can weaken the entire ecosystem.

Further, garlic mustard’s roots release chemicals that alter the important underground network of fungi that connect nutrients between native plants, inhibiting the growth of important species like trees.

Another common plant at this year is Galium aparine (‘aparine’ from Greek ‘apairo’ [απαίρω < από «from» + αίρω «pull to lift»] – “lay hold of” or “seize”) with many common names including hitchhikers, cleavers, clivers, bedstraw, goosegrass, catchweed, stickyweed, sticky bob, stickybud, stickyback, robin-run-the-hedge, sticky willy, sticky willow, stickyjack, stickeljack, grip grass, sticky grass, bobby buttons, whippysticks and velcro plant. Dioscorides reported that ancient Greek shepherds would use the barbed stems of cleavers to make a “rough sieve”, which could be used to strain milk. Carl Linnaeus later reported the same usage in Sweden. In Europe, the dried, matted foliage of the plant was once used to stuff mattresses. Children in the British isles have historically used cleavers as a form of entertainment. The tendency for the leaves and stems to adhere to clothing is used in various forms of play, such as mock camouflage and various pranks.

Riding into a village, I saw that today I was back in the land of huge houses, double garages, blossom trees and fountains on the lawn. One home had a beautiful cedar tree whose boughs spread far across the lawn. Next door was a tall monkey puzzle tree. Cedar trees are native to the mountains of the western Himalayas and the Mediterranean region, occurring at altitudes of 1,500–3,200 m in the Himalayas and 1,000–2,200 m in the Mediterranean. They always remind me of the flag of Lebanon.

In 1943 Lebanon gained independence and adopted a flag made up of a white field with two horizontal red stripes at the top and bottom with a green cedar tree in the centre. The red represent the blood shed and white represents purity and peace. The cedar represents the Bible. (The cedar of Lebanon is mentioned 77 times in the Bible.)

During the Phoenician era, between 3000 BC – 200 AD, the main flag was the blue-red bicolour flag. In 200 AD the main flag was that of the Tanukh tribe. A white-blue-yellow-red-green vertical banded flag. In 750 a plain black flag was adopted under the control of the Abbasid Caliphate. Part of Lebanon was part of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1099 and had a flag made of a white field with a large gold cross and three smaller crosses.

Between 1119 and 1697 part of Lebanon were controlled by the Banu Ma’an tribe. The flag was a white-red diagonal bicolour with laurel wreath. In 1282 the Ayyubid Dynasty had some control adopting a plain yellow field. The Mamluk Sultanate had control of the area from 1250 and used a flag featuring a Egyptian yellow field with left facing crescent moon. From 1697 the flag of the Chehab Empire adopted a plain blue field with right facing crescent moon.

The Ottoman Empire ruled Lebanon between 1516 and 1918. The flag features a red field with white crescent moon and five-pointed star. After the fall of the Lebanon Empire there was a new flag adopted featuring a white field with a green Lebanon Cedar tree in the centre. In 1920 the French took control of Lebanon. They adopted three flags featuring a blue, white, red vertical tricolour with a green cedar tree, one with a black cedar tree and one with green leaves and a brown stem. I wonder what will be next?

Meanwhile, the monkey puzzle next door originates from central and southern Chile and western Argentina. It was first brought to the UK in 1795. It became very popular during the Victorian and Edwardian era and is now widely planted as an ornamental in parks and gardens. Distinctive and spiky, the monkey puzzle has been making strong impressions since dinosaurs roamed the earth. These days, jays and squirrels feast on its nuts. This species has been around for 200 million years. Its spine-like needles acted as protection from ancient grazing animals.

8400 miles away from Lebanon’s cedar tree, the flag of Chile is a white and red horizontal bicolour with a blue square in the top left corner inside of which is a white five-pointed star. The first flag flown in Chile was the war flag of the Mapuche. The flag is a plain blue field with a white eight-pointed star, called guñelve in the centre. At this time the burgundy cross flag was flown by the invading Spanish army in Chile.

When the Spanish took control of Chili in 1785 the country adopted the Spanish national flag. At the time it was a horizontal banded red-yellow-red flag with the Spanish coat of arms in the centre left.

When Chile gained independence in 1812 ‘Patria Vieja’ flag was adopted. This was a simple blue, white and yellow horizontal tricolour. The English translation of Patria Vieja is ‘our fatherland’. An alternative Patria Vieja flag was also chosen that reverses the white and blue bands and adds the Chilean shield and Cross of Santiago in the top left hand corner.

In 1814 the Army of the Andes were holding military campaigns in Chile. The flag flown was a white and blue bicolour with the coat of arms of Argentina in the centre. In 1817 the national flag of Chile was changed again to a blue-white-red horizontal tricolour and in 1918 a new tricolour was proposed with the blue and white bands swapped and a white five-pointed star in the centre.

In 1818 the flag was changed again to feature a white and red horizontal bicolour with coat of arms in the centre and a blue square with white five-pointed cross in the left hand corner. The coat of arms was removed in 1934 and is still flown today. The flag can be displayed either horizontally or vertically. I wonder what will be next?

The homes in the centre of the village were not big, but they were very old and charming, clustered around a couple of appealing pubs (‘it’s too early, Al. It’s too early’.) One was called ‘The old chemist’, another the ‘Old butchers’. It’s a nod to the huge change in usage of village buildings over the centuries. Today’s occupants probably work in IT in London and have their food delivered from a supermarket warehouse somewhere Also, I presume the old butcher wasn’t rich, yet now his quaint old building is worth a fortune.

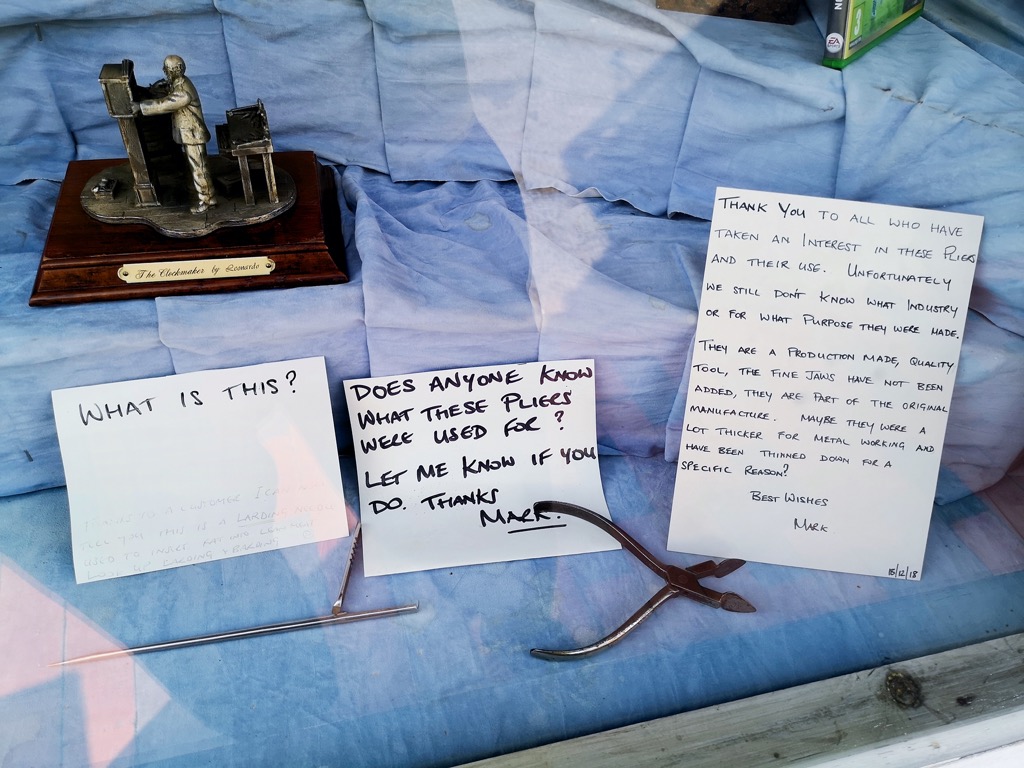

There was an antique watch restorer in the village, with his window displaying the perfect A Single Map ephemera. An unusual pair of antique pliers had an attached note asking ‘Does anyone know what these pliers were used for? Let me know if you do. Thanks, Mark.’ Alongside a strange spiky thing a note asked simply, ‘WHAT IS THIS?’

Updates to the mystery had been added: a note from December 2018 informed us, ‘Thank you to all who have taken an interest in these pliers and their use. Unfortunately we still don’t know what industry or for what purpose they were made. They are a production made, quality tool, the fine jaws have not been added, they are part of the original manufacture. Maybe they were a lot thicker for metal working and have been thinned down for a specific reason? Best wishes, Mark.’

Fortunately, the mystery of the strange spiky thing had been solved. ‘Thanks to a customer I can now tell you that this is a LARDING needle used to inject fat into lean meat. Look up larding and barding. 🙂’

OK, Mark, I shall!

Larding beef means to artificially marble the meat with fat. The fat is introduced in the beef’s cut using a larding needle. The fat injected can be beef fat or more likely pork fat. Barding beef engages wrapping the meat in two or more strips of fat which have the purpose of protecting the meat from drying. There are people who confuse larding beef with barding beef but the difference is very clear.

I pedalled out of the village, down a grassy byway towards a patch of woodland by the motorway. The big oak trees had their first blush of unfurling green leaves, and a little wren was blasting out its surprisingly loud song. Plump, short and loud-mouthed, the wren is one of our most common breeding birds. Though it’s small in size, it makes up for it with its powerful song. Wrens are small, short birds, measuring just 6-10cm in length. Each male uses moss and twigs to build a selection of domed nests for females to consider when they enter the male’s territory. If a female chooses a certain male’s nest, they will begin breeding once the nest has been lined. More often heard than seen, your best chance of identifying this little bird is by listening out for its loud song. For such a small bird, it has an incredibly powerful voice! The loud song from such a small throat is possible because birds have an organ called a syrinx with a resonating chamber and membranes that utilise virtually all the air in the lungs and can produce two notes at the same time. I began to notice it once someone told me that each burst of song ends with a machine gun-like trill.

Tiny patches of woodland nestled against motorways are fast becoming one of my favourite features of my map. The soft subtle shades, the stillness, the birdsong; they all lull you. And then you step out to the roar of metal, bright primary colours, the tang of burning fuel and the harsh open sky.

I crossed the motorway on a narrow footbridge. I was impressed by it, for it must have cost a fortune and seemed little used. It would have been easy for the government to simply have ignored this ancient footpath and made the right of way a redundant dead end once the motorway was built. But instead in England and Wales there are estimated to be 140,000 miles (225,000km) of public rights of way, consisting mainly of footpaths, but including bridleways and other types of byways. The figure for Scotland is estimated to be 9,300 miles (15,000km).

Rights of way are a network, the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs says, comprising “a mix of age-old routes, including those created statutorily as part of the process of enclosing the old common lands land into private occupation and those created more recently, either through long public use, or under statutory powers, or through dedication by the landowner”.

Rambling became popular in the 19th Century among town-dwellers keen to get some fresh air and exercise, escaping their often polluted home environments. The romantic poets, who emphasised the power of nature, encouraged walking. William Wordsworth and John Keats were among those who took long strolls for inspiration.

As long ago as 1949, the government began documenting public rights of way in England, their origins and exact whereabouts sometimes murky, in an effort to make sure those less well documented didn’t die out. “That process proved far more difficult than originally envisaged and remains unfulfilled to this day,” the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs has said.

In 2000, the government set a 2026 cut-off time for rights of way to be registered – 77 years in total after the process started. And, in 2012, the coalition promised to make it easier and quicker to register paths, so that fewer would miss the final deadline and be lost for good.

But the RA says monitoring efforts require still greater urgency, in case some of the undiscovered rights of way become null and void. It has launched the Big Pathwatch scheme, asking members to compile a full log of the state of public rights of way in England and Wales. An app allows people to share their experiences as they walk every right of way within a specific grid square.

Fixed to the motorway bridge were notices advertising The Samaritans. ‘Talk to us, we’ll listen,’ they say. ‘Whatever you’re going through, you don’t have to face it alone. Call free day or night on 116123.’ On their website, the Samaritans say, ‘Whatever you’re facing, a Samaritan will face it with you. Every day, Samaritans volunteers respond to around 10,000 calls for help. We’re here, day or night, for anyone who’s struggling to cope, who needs someone to listen without judgement or pressure.

Samaritans is not only for the moment of crisis, we’re taking action to prevent the crisis. We give people ways to cope and the skills to be there for others. And we encourage, promote and celebrate those moments of connection between people that can save lives. We offer listening and support to people and communities in times of need. In prisons, schools, hospitals and on the rail network, Samaritans are working with people who are going through a difficult time and training others to do the same.

Every life lost to suicide is a tragedy, and Samaritans’ vision is that fewer people die by suicide. Every year, Samaritans volunteers spend over one million hours answering calls for help via our unique 24-hour listening service, email, letter, face to face and through our Welsh language service.

On 2nd November 1953, Chad Varah, a vicar and writer-cartoonist, answered the first ever call to a brand new helpline for people contemplating suicide. For many years, Chad would work all day and stay up until 2am or 3am writing scripts and cartoons to make ends meet. In his own words, his church stipend was only enough to pay Vivan Prosser, his secretary .

But, in the summer of 1953, Chad was offered charge of the parish of St Stephen in the City of London, a post which gave him the time he needed to launch what he called a ‘999 for the suicidal’.

Over the motorway now, into fields, and the landscape felt totally different. This was heathland, at least for a couple of fields’ span before the tall fences of the quarry began. The earth was baked dry, hard and cracked like Africa. It’s not what you expect in England in April, though this has been a particularly dry and cold April.

I noticed that I was hurrying and rushing, for no good reason. I want these outings to be a pleasure, not a mission. I also noticed that the sky was a deep blue with clouds scudding swiftly in the high altitude winds. So I lay down in the field and stared up at the clouds for a few minutes to relax. It felt good to have the sun on my face. I studied the clouds and imagined the shapes I could see.

“Do you see yonder cloud that’s almost in shape of a camel?

Polonius: By the mass, and ‘tis like a camel, indeed.

Hamlet: Methinks it is like a weasel.

Polonius: It is backed like a weasel.

Hamlet: Or like a whale?

Polonius: Very like a whale.”

I’m not the only person to appreciate clouds. The Cloud Appreciation Society does just that. Their manifesto declares:

WE BELIEVE that clouds are unjustly maligned and that life would be immeasurably poorer without them.

We think that they are Nature’s poetry, and the most egalitarian of her displays, since everyone can have a fantastic view of them.

We pledge to fight ‘blue-sky thinking’ wherever we find it. Life would be dull if we had to look up at cloudless monotony day after day.

We seek to remind people that clouds are expressions of the atmosphere’s moods, and can be read like those of a person’s countenance.

We believe that clouds are for dreamers and their contemplation benefits the soul. Indeed, all who consider the shapes they see in them will save money on psychoanalysis bills.

And so we say to all who’ll listen:

Look up, marvel at the ephemeral beauty, and always remember to live life with your head in the clouds!

The enormous quarry has gouged 20 metres out of the earth. I read that it produces building sand, silica sand, top soil, southern side sand, equestrian sand and reject sand. For building sand, when soft sand is used, the mortar is very smooth and plastic and it is much easier to spread and to bed the bricks in than a mortar made of sharp or clean sand. Naturally the bricklayer prefers to use a mortar made with soft or unwashed sand, often called ‘builders’ sand’. A good washed sand for mortar should, if clenched in the hand, leave no trace of yellow clay stains on the palm.

Silica sand is a very durable mineral resistant to heat and chemical attack and it is these properties that have made it industrially interesting to man. The first industrial uses of crystalline silica were probably related to metallurgical and glass making activities a few thousand years BC. It has continued to support human development throughout history, being a key raw material in the industrial revolution especially in the glass, foundry and ceramics industries. Silica contributes to today’s information technology revolution being used in the plastics of computer mice and providing the raw material for silicon chips. For industrial use, pure deposits of silica sand capable of yielding products of at least 95% silica are required. Often much higher purity values are needed. Deposits where such sand can be found are comparatively rare in the UK.

Reject sand is mainly Silica based and is a bi-product of the washing process. They often supply this to farmers who use it as a bedding material for cattle. Topsoil is the top layer of the earth’s surface. Topsoil is dark in colour and high in organic matter, which makes it very easy to till and fertilize ground for growing plants. It is scraped from the ground and sold in bags or bulk, often called “black dirt”. (As an aside, in the US alone, soil on cropland is eroding 10 times faster than it can be replenished.If we continue to degrade the soil at the rate we are now, the world could run out of topsoil in about 60 years.)

Looking down into the quarry felt shocking, that such a big hole could be manmade, and that we were literally removing the landscape. I know that my map has been built on extensively. But I’m used to the sight of towns, roads and industry. It’s another example of shifting baseline syndrome. (Show a caveman around my map and he would be awestruck and probably terrified by the crowds, the noise, and the concrete covering his Eden.) Seeing this huge hole in the ground made me feel a little different, more aware about the impact of our endless desire for ‘development’.

On the other hand… When extracting minerals, we change the landscape and at first glance would appear to destroy nature and undermine biodiversity. Yet quarries can actually provide important habitats for plants and animals that are being increasingly displaced by development in other areas, both during the active phase and also through reclamation to nature habitats.

Quarries can provide a dynamic mosaic of habitats at different stages of succession, and landforms that provide an interesting microtopography with unique climatic conditions. Through the active process of the quarry, these features are often transient in nature, occurring in different parts of the site at different times.

These ecological niches offer animals and plants an area of retreat that they would rarely find nowadays outside our quarries. Some examples of these species are: sand martin, bee eater, eagle owl and peregrine falcon, yellow-bellied toad, natterjack toad as well as the bee orchid and other rare orchids.

Hopefully, no matter how much humans think they’re ruining the planet, the natural world will ultimately prevail. If you want to protect nature, the best thing to do is nothing.

Comments