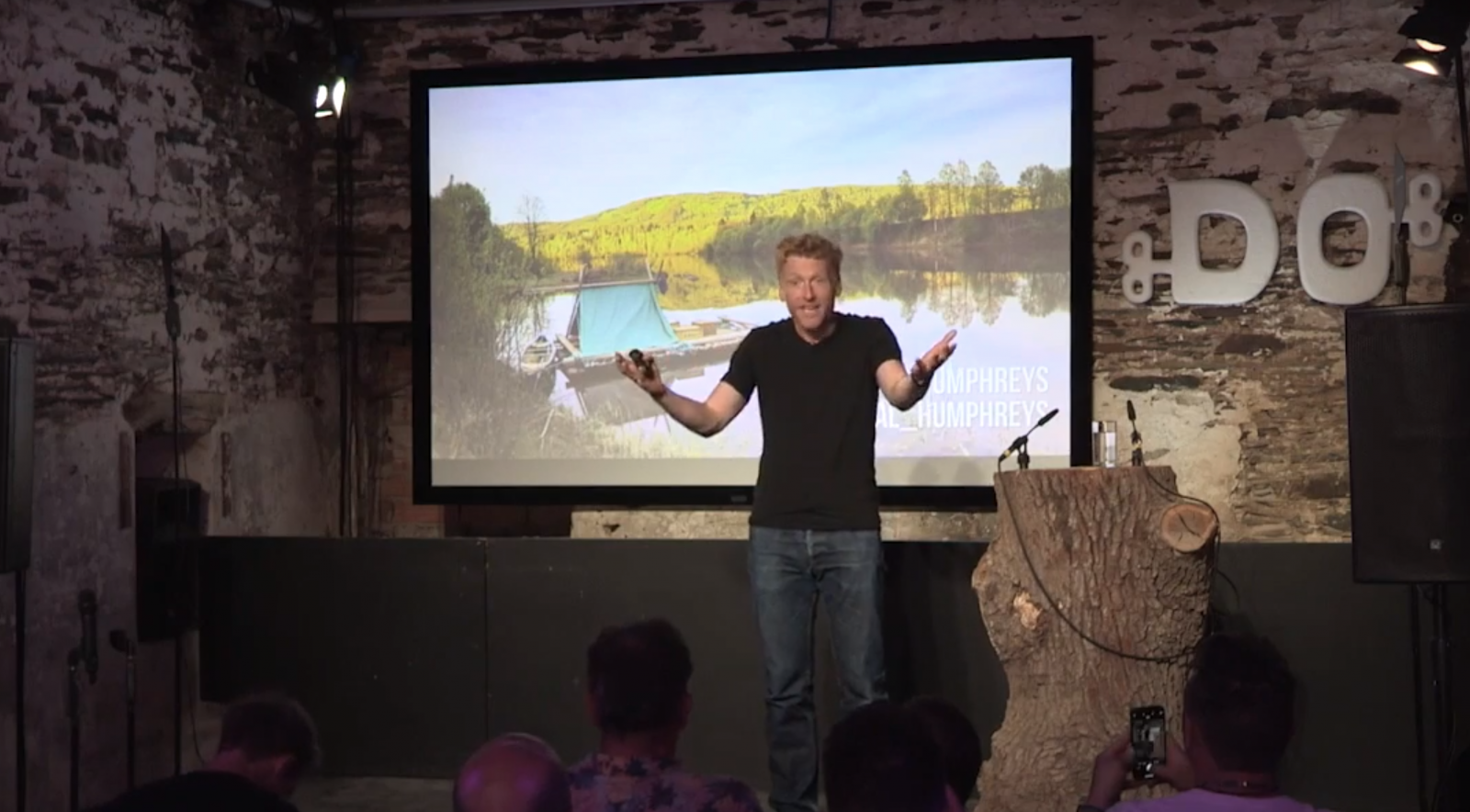

One of my favourite speaking events was the Do Lectures in Wales.

Here’s my talk, followed by the transcript.

Let me ask you two questions.

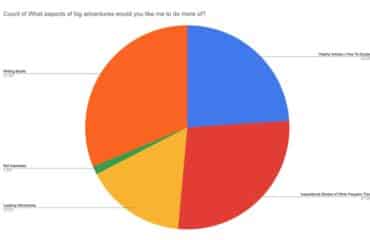

The first: ‘would you like to live more adventurously?’

I don’t mean would you like to go on big, massive, epic adventures. I mean would you like to just live a little more adventurously every day? What that might involve is up to you. It could be learning how to make your own chutney or grow some chillis. It could be taking more risks with your business. It might be learning salsa dancing. It doesn’t matter. I’m suggesting whatever feels interesting and fulfilling to you. So, would you like to live more adventurously? I know that I certainly would.

The second question then is, ‘what’s stopping you?’

I think there are probably two things. One is probably a practical reason. If I was to guess, I’d plump for a lack of either Time or Money: these are usually what stands in our way at different times of our lives. The second thing that might be stopping you living more adventurously is perhaps a little bit more intangible. It might well be something that you’re a bit shy or embarrassed to admit to. If I had to try and guess one or two, I might go for feeling inadequate or worrying what people think about you or just pure old guilt. They’re my usual three, anyway!

How then can we get ourselves to live a little bit more adventurously? Over years of intelligent philosophical reflection, I have concluded that living adventurously is essentially the same as going skinny dipping in a river. It sounds exciting and thrilling to do, but it feels rather daunting.

You think, “Oh, respectable people like me don’t do stuff like this.” You stand on the river bank feeling a bit nervous. Vulnerable. You summon up the will to dip your toe in the water. But the first step is cold and horrible! (That never changes, by the way.) But you persevere, and little by little, step by little step, tiptoeing and yelping, you creep into the water, and before you know it you’re in there, you’re swimming! And then all of a sudden you’re now the expert, the guy in the river, doing it, swimming, grinning, whooping and hollering and shouting to all those timid souls on the riverbank like an expert, “Come on in, it’s great once you’re in. Stop being such a wimp. All you gotta do is get in! Once you start, you won’t regret it….”

I want to talk about why I think Living Adventurously is relevant to all of us, even if you think that being sweaty, thirsty, hungry, alone and lost in a desert is not your idea of fun. It is often only a small jump like this that stands between where we are now and where we want to be. That’s all we have to do. You like the idea of being in that river, but it’s hard to get in. The Scandinavians have a wonderful phrase that encapsulates how difficult it is to start a journey, how hard it is to set out from your warm, comfortable, familiar house into the cold, scary, great outdoors. They call it the doorstep mile. Crossing the threshold, stepping across the doorstep and beginning, is the longest mile of any journey.

I wish that I had known about the Doorstep Mile before I began my own adventures. I used to really beat myself up for how hard I found it to start journeys. I used to think I was lazy, that I was a coward, that I was pathetic just because I found it so hard to get going. But there’s a world of difference between a blank page — so much to do, inertia — and then one little cross in the box, one item ticked off, one sentence written, one mile walked, one day done. You’ve done it. You’re on your way. You’ve got momentum now, and from then on, it is pretty easy to get to this — completion, success. All you have to do is not stop. That sounds glib and trite, but once you are flying you will know it to be true. It has certainly been the case on every expedition I have ever been on.

I want at this point to debunk the myth that to be an adventurer you have to be some sort of Olympian, athletic, tough guy. That is definitely not me. I spent most of my student days being very lazy, mucking about until I gradually came to decide that before I settled down to an ordinary life and job like all of my friends, I should try to do something out of the ordinary and difficult. So I took my £7000 of life savings and set off to cycle around the world. It turned into a four-year journey riding 46,000 miles across five continents. That’s an easy thing to say. Travelling the world is a pretty normal daydream for people to have. But I look back at the young me with astonishment and gratitude that I actually took the hardest step of all – beginning. I didn’t really think about whether I could actually cycle round the world. (In fact I was convinced for the first 2.5 years that I wouldn’t make it all the way.) But I made it. It was the most wonderful, wild, overwhelming, exhausting experience of my life. I was not any sort of specialist, but once I got home, I did now have the three most important secret weapons. These were self-confidence, experience, and momentum. I was on my way.

This led on to me doing many more adventures over the coming years. I ran the 150-mile Marathon des Sables in the Sahara Desert because I liked pushing myself hard, the ferocious heat, the tightly rationed water, the camaraderie of sharing the suffering with so many other competitiors; On the other hand I crossed Iceland from coast to coast for the blissful unspoiled isolation and beauty, carrying everything we needed for a month; 40kg of kit, constant hunger. By deliberate contrast I walked coast to coast across southern India for the people, for all the reasons travellers have always been drawn to India: a billion friendly people and all their stories squashed into the chaotic noise and disorder and stench and laughter and fabulous food and tea and cricket of India. I crossed the Empty Quarter desert because of the historical lure of adventure literature. And I rowed across the Atlantic Ocean because — I don’t actually know why! We were just 4 guys in a tiny boat, thousands of miles from land or help, totally out my depth, in every way. I remember fear, grinding seasickness, tedium, pain, trust, growing confidence, hysterical laughter, and the deep bond of sharing something difficult together. I generally launched off into a life filled with epic experiences, a life filled with hard, elite expeditions. It was all building towards an epic journey to the South Pole.

That led eventually to a little red tent somewhere in the mountains in Eastern Greenland. We had been dropped off by ski plane, hundreds of miles from the nearest human. I was there with two of my friends. There we were in our tent, just the three of us. We carried a rifle because of the risk of polar bear attacks. It was cold, it was remote, and there were potentially dangerous crevasses all over the place. But it was such a happy tent – one of the most beautiful, harmonious, remote, thrilling, laughter-filled expeditions of my life. I was so happy out there. Everything was coming together. I was doing what I loved, doing epic stuff, I’d managed to turn my hobby into my job, and I was mixing it now with the best of the best. But suddenly in that little red tent, everything went wrong, and my dreams of an adventure-filled life came crashing down.

We had just finished a long day hauling our heavy sledges. We’d set up camp, the three of us in there. We were in our sleeping bags, three good friends tucked up warm against the cold. The stove was on, that delightful low roar that promised hot food and drinks to come. It was my turn to cook so I was fiddling about with the stove, melting snow, preparing dehydrated chicken curry. I was doing what I loved with my life. I had managed to turn my hobby, my passion into my whole life. We were laughing together. It was wonderful.

And then in that little red tent hundreds of miles from anywhere, my good friend Ben made some lighthearted throwaway comment. I don’t even really remember what the context was, but he made a joke about how I was a terrible dad for being out there on this expedition rather than being at home with my wife and children. To all of our surprises, not least of all mine, I promptly burst into tears, great howling guilt-wracked sobs. Because, as much as I was living a personally thrilling and fulfilling life of expeditions and travel, it was wreaking havoc with my family life — with my real life. I had left behind at home my little son, my daughter, and my wife. I felt sad at leaving my family, I felt guilty at the extra burden this trip placed on my already-exhausted wife, and I felt vain and selfish chasing adventure dreams that were undeniably dangerous. It suddenly dawned on me, “what on earth am I doing?”

That was all that happened. And three British guys in a tent, we aren’t very good at dealing with someone crying, so we all just did our very best to quickly ignore the whole episode and get back to taking the Mickey out of each other as soon as we possibly could, strapped on our skis the next morning and continued hauling our sleds across the icecap. And that was it. That is the sum total of my grand life-changing catastrophe story, which I know is pretty feeble and pathetic. What had happened? Real life happened. That was all.

Real life brought all my dreams crashing down, all my plans and hopes and ambitions. I pulled out of the South Pole trip and all future huge expeditions. I called myself an adventurer, but I was no longer going on Adventures. All of my dreams had gone. I felt ashamed. I felt disappointed. I was so frustrated, and I became really unhappy.

So, all I have to offer you then is this: that for every Steve Jobs or Bear Grylls hero success story, for every inspiring follow-your-dreams, reach-for-the-stars story, I reckon there’s a million of us squashed together in that same little red tent, reaching big, chasing dreams, reading the good books, doing all the right stuff, but nonetheless stymied and frustrated by real life.

What can we do about that? How can we still live adventurously but within the constraints of real life?

I found my adventurous life changing. I had spent years trying to do bigger, tougher, harder journeys than anyone else, to feel special by striving to be elite, trying to be the best adventurer there was. My direction changed towards adventures that were smaller and smaller and ever more inclusive. From trying to go further than everyone else, I shifted to saying, “you’d love to cycle around the world, but that’s not going to happen. Why not try this instead?” You can’t afford to cross a continent? What is within reach? You don’t have time to do an adventure? What can you do? You can still do something. You can always do something. I called these little adventures microadventures.

Everything that happens in life, you can see as either an opportunity or a constraint. You can either complain about how little time you’ve got to do things or you can try and squeeze in something around the margins of your life and still do something. (By the way, if you try and claim that you are too busy to go for a ride in the woods or to head up a hill to watch the sunset, then I politely say to you that that is ridiculous and what you really, really need to do if you’re too busy for that is go immediately for a ride in the woods or a walk up a hill!)

I had a tedious eight-hour journey to get here yesterday evening. I was tired and nervous about having to do this talk this morning. But I still made the effort to squeeze in time for a little microadventure escape. It has become a habit. I slept up on a beautiful hill last night, the stars were great. And I found a quiet pool for a little swim this morning before the talks began. It is always possible to do something.

Let me give you a microadventure example from real life. My wife and I put our kids to bed in the evening. From time to time, I will then grab my sleeping bag, my camping gear, and head up the nearest hill — hopefully one without any phone reception at all — and sleep under the stars. (My wife, by the way, prefers a hot bath, a very comfy bed and WhatsApp chats with her friends. She thinks I’m a total idiot.) I sleep on the hill, wake to the sunrise, run back down the hill, jump in a river, then head back home again in time to do the school run. As well as being fun, I am also a much calmer person for this time outdoors, better able to give of myself, to be a better person, a kinder husband, and a much more patient father. This is how I squeeze some adventure and time in nature into my normal life.

This tiny five-to-nine overnight microadventures is no big deal. Of course not. But it is a short little hit of all the good stuff, the stuff that feels really important in my life. In the same way that having a sip of espresso is not the same as having a massive latte, but it kind of tastes the same. It still gives you a buzz. It still gives you the hit.

I started trying to encourage other people to do similar things, searching for wilderness wherever they happened to live, making the most of their weekends, getting out with their kids into the great outdoors and making it easier to do that activities that feel important to you. It doesn’t really matter what that is. It might be running or biking or swimming or hiking or rafting or paddling or tubing or foraging or cooking or staying in bothies, or just sleeping or even walking a lap of the M25 just to explore the local wilderness if that is where you happen to live.

It doesn’t even have to be active adventure. I’m not didactic about this stuff. I mean, you could be out there painting or restoring walls or lighting fires or baking bread or eating takeaway curry in caves. It doesn’t matter what you do just so long as you do something. We can always find the time and the opportunity to do something if we choose to do so.

Essentially, what I have tried to do is make microadventures so small and so simple as a way to tackle the barriers of real life. This is your problem? OK, try this. Still too hard? OK, try this. I kept reducing and simplifying and trying to put a positive spin on every situation. Think smaller and simpler! Look around you! What can you do in your lunch break? Climb a tree, make coffee in the woods, jump in a river. When you’re driving you can use your Sat Nav as an adventure guide – look for rivers to detour to rather than service stations. And if people still push back with the argument, “it’s easy for you to say. I can’t do this because…” then at some point there becomes nothing more that anyone can do. And then I just have to say — in the most polite voice that I can muster — “I’m sorry. There’s nothing more I can do for you. It’s time for you now to look in the mirror, and be a little more honest about what fears and excuses and vulnerabilities are stopping you from getting out there across the doorstep.”

Microadventures proved to be incredibly popular – dozens of regional Facebook groups began organising community microadventures; responsible adults were buying bivvy bags then leaving their offices to sleep on top of a hill for the night. I got emails from people who were divorcing or depressed or overweight or overworked who really connected with the idea, lovely stories of families having adventures together.

My perception of adventure has changed so much now that I no longer see adventure as being the exclusive domain of rugged men doing rugged stuff in rugged places. Adventure is so much broader than that. Living adventurously really is about the attitude that you choose to charge at life with: doing stuff that is new and different, that scares you and makes you curious. If you think that is a good attitude to live with it can apply to all of us, even if you are someone who thinks that the idea of sleeping in a tent is very stupid.

Living adventurously is being curious to look differently at the world, try new things, and risk looking like a fool. A combination of age, momentum and experience of how good trying to live more adventurously makes me feel that I am now more than happy to be regarded as a weirdo. I sleep without a tent on hilltops whilst many of my old friends are worrying about the wine list in gastro pubs. I love turning up to meetings in London reeking of woodsmoke. I often turn up to give serious corporate presentations with wet hair and going commando under my suit after jumping in a nearby river and towelling myself off with my boxer shorts. This mindset undoubtedly makes me happier.

However, these big adventures created a problem in my own life. I have been doing adventurous activities like biking and hiking for about 20 years now. I’m good at it. I’m familiar with it. It is a world that I knew well. But if adventure is about fearing failure and uncertainty and risking stuff, then carrying on doing more and more of the same things that I’ve been doing for so long, the sports that I was good at, well that’s not living adventurously anymore. That’s just resting in a safe, easy comfort zone. So if I wanted to keep living adventurously myself, I needed to think very differently about what that now meant for me. It was time to change direction.

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning is my favourite ever travel book. A young man walked through Spain in the 1930s, playing his violin to fund his journey. It is a beautiful bucolic story, and ever since I first read it, about 15 years ago, I thought to myself, “I would love to go and do that journey.” But I can’t play the violin or any other musical instrument. The idea of having to play music or sing karaoke or dance is my idea of absolute hell. So clearly I couldn’t go and do this exact trip.

But I couldn’t quite get the idea out of my head. This idea scared me so much, I couldn’t play the violin. I would almost certainly fail. It was a ridiculous suggestion. And so on a whim, before I had time to think about what I was doing, I got out my phone and googled a for local violin teacher. Quick as a flash, I sent an email,

“Dear Mrs. Violin teacher, I really want to walk across Spain next summer, with no money and no credit card, only my violin. Please can you teach me enough violin songs in the next seven months so that I do not starve to death? Your sincerely, Alastair Humphreys.”

Send. Easy as that.

Forget all about it.

Ding, an email arrives.

“Dear Mr. Humphreys, this is a very stupid idea. The violin is a lifelong craft. You cannot possibly learn to play in seven months. This is a very stupid idea. You will definitely starve to death.

Come to my house tomorrow morning and we will begin.”

Well, I turned up at this lady’s house, and I quickly learned that the violin cannot be quickly learned. I had totally overestimated how much I would be able to learn in seven months. Unfortunately, as my anticipated departure date approached, I had to face the sorry fact that I really could not play the violin very well at all. The sensible thing to do was either to go to Spain as planned, but just with all my cash and just play the violin for a bit of a laugh. Or to postpone the trip for a year or two until I could actually play the violin quite well. Fortunately in life, the only sensible option is not the only option. And so I jumped on a plane and began. I emptied the final few coins from my pocket, left them on a park bench and walked off into Spain one midsummer morning to see if I could survive for a month with no money and only my busking skills.

The very first time I set up my violin to play — oh, God, it makes me nervous to think about it — I really wanted to scare myself, really wanted to be out of my depth and therefore I’d deliberately not done any busking in the UK before I began. In fact, I hadn’t played my violin in front of anyone except my violin teacher — and I’d paid her for the privilege. On this day, as I set up my violin case, tuned the instrument, and got ready to begin, I realised that I was the most scared I had felt since the day I set off to row across the Atlantic Ocean.

Isn’t that crazy? Rowing the Atlantic Ocean is quite a frightening thing to do. There’s sharks and storms and capsizes. And what was I scared of here? What I was afraid of was all inside me, all my internal vulnerabilities. The things that we hide away and hide behind. The things that so often stop us doing stuff and living as adventurously as we dream of doing. What, specifically, was worrying me? I was scared of failing, certainly, and failing seemed pretty likely. I was definitely nervous about that. But more immediately I was worried about what would people think about me. What if someone says something mean to me? What if someone is unkind? What am I doing here? Respectable, sensible grownups are not supposed to behave like this? This is so embarrassing. Am I a weirdo?

This was undeniably pathetic behaviour for a grown man in his 30s. But I was getting hungry and there was no plan B. All that I could do was pick up my violin, trust the universe and begin.

I was convinced that I was going to starve in Spain because, to reinforce my earlier point that I’m not some sort of superman adventurer, I had no idea how to forage or catch wild animals. I do my foraging in supermarkets. If I didn’t earn some cash, I was going to fail. So when I found on the road a discarded ketchup sachet, I snatched it up and I ate it down like one of those expensive cyclist energy gels. Oh, free food, free food! This is what I need! That first morning in Spain was some of the worst few hours of my life, standing in that town square, sawing away. I could hack my way through five songs, very badly. They were each about 30 seconds long and I just looped round and round through all five.

An elderly gentleman had been sitting on a bench listening to me for quite a long time. He eventually stood up. He walked over to me with his walking stick and I thought, “Uh-oh, I’m in trouble now. He’s going to say, ‘Señor, enough. Clear off. Please, give us back our peace.'”

But he didn’t say that.

Instead, he reached into his pocket and he pulled out a coin and he gave it to me. And I thought my heart was just going to explode with delight, relief, amusement, and surprise. I’d done it! I’d earned a coin.

Before the trip began, I had been really freaking out and I’d got to the point where I was on the verge of scaring myself out of doing it. I made myself a deal. I said, “Don’t worry about the whole trip. Just go out there and get one Euro. It’s all you need to do, get one Euro. If you get a Euro, you can buy a bag of rice. If you buy a bag of rice, you can walk for a week and then we’ll talk.” And here in this one instance, he’d given me a Euro, a bag of rice, but much, much more than that: he had given me hope.

And so now I set off walking out into Spain one summer morning just like Laurie Lee had done eighty years ago. I spent a month following my nose cross country through beautiful wild landscapes, dropping down into villages every couple of days to busk and earn enough money for the next stage. The hiking and camping was not the adventure, the long miles, cooking on fires, the stuff that I’d been doing for 20 years. This was not the adventure at all. The violin was the adventure.

The journey was an absolute triumph. I lived like a king. Some days I even earned more than three Euros! In a month, I earned 125 Euros. No man needs 125 Euros in a month. I lived off carrots and banana sandwiches. I was very happy. And then one glorious day, I found in a bin in a park a discarded tub of pork scratchings. Life had reached a high level of joy. Whether you share my excitement or are repulsed probably depends upon how hungry you have ever been.

And what about the thing that I was so scared of before I began, the other people. The fears about ‘What will people think?’ Well, that turned into being the great joy of the whole experience, to turn up in little villages, screech away with my violin, and to witness people respond to that. I think they recognised someone who was putting himself out there. It prompted complete strangers to help me out and send me on my way. Walking through the mountains of Spain for a whole month was a glorious, glorious experience.

The hundreds of miles of hiking, the river crossings, the campsites on hill tops or river banks was not what made this adventure special. I’ve done that stuff all my life. The adventure for me, was standing up in a plaza in front of a handful of people and saying, “Here I am. This is my best shot. This is all that I have got.”

Busking through Spain was one of the very best adventures of my life, and I really hope that it will encourage you that living adventurously can apply to all of us. Whether you choose to cycle around the world, walk around your home town or just learn a musical instrument, we can all live a little bit more adventurously in our life.

I spent years trying to do huge journeys and ultimately, I failed. So as someone who fell short with my ambitious dreams, but eventually has come out smiling the other side, I want to finish now by offering a couple of suggestions. The first is this. I don’t think that we should pin our hopes on trying to have one huge big adventure of a lifetime, but rather we should try to live a little bit adventurously every day. Doing whatever excites us, makes us happy, makes us fulfilled, makes us curious, and makes us a little bit scared.

And the second aspect of trying to live more adventurously that follows on from that is that we need to do something small every single day we are to fully be living adventurously. I have a challenge for you today. Actually, I have two challenges. First one: go jump in a river. It’s good for the soul. The second thing goes back to the doorstep mile, that tiny little step that gets us out on the cold, difficult journey. What is your doorstep mile? What tiny little thing can you do today? The email to a violin teacher. The chat with your friend about that thing you always talk about when it’s late in the pub, a meeting with someone at work about a new project. It has to be really small. So small that there is no reason not to do it today (except for your own wimpishness). What tiny little thing can you do — today — that will set you in motion?

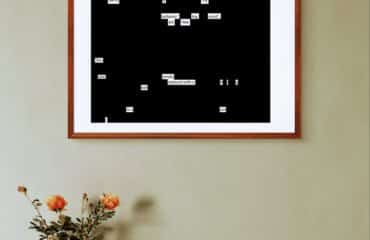

And if you’re still procrastinating on even something as small as that, then I want to finish up by sharing with you one of my favourite websites. Check out deathclock.com. Death Clock calculates the date of your death so that you can stick it in your diary, and if you’re the sort of lazy procrastinating person who needs a deadline to get something done, jeez, there it is, my death and all days following. I had better get on with life, there’s not long left.

And so to the cheerful view of my life ticking away with deathclock.com, I thought I should do something, finish my talk by doing something that scares me, that excites me, that amuses me, that feels to me like living adventurously. Ladies and gentlemen, coming to you live, the world famous violin. So I’ve been talking for a while quite happily. I’m now sweaty and nervous and so should you be. Here we go…

Comments