Commit! Begin! It’s easier said than done, of course.

If you’re hankering to do something big, let’s take a look at how to make it a little more achievable.

Things that seem very different often have much in common. You can learn from many different people’s approach to life. It’s a reason to experience things very different from your own chosen route, to take a look at the same problem from a fresh angle.

Earlier in the year that I walked from Salalah to Dubai, I rowed across the Atlantic Ocean. I was struck that the two journeys were so similar and the obvious differences (blue, wobbly, wet versus brown, still, dry) in fact didn’t count for nearly so much. The similarities included the discomfort, the hostile environment, the slowed-down hours, the banter.

But in one important aspect, rowing the Atlantic Ocean was unlike any other journey or project I have ever undertaken. There are, clearly, a number of things that could go really quite wrong when you head out into 3000 miles of ocean in a 9 metre rowing boat.

(In actual fact, so long as you keep attached to the boat and keep the hatches shut, then nothing catastrophically bad should happen. It’s a great example of perceived risk and fear versus real danger. So too is being eaten by a shark.

But still, there is the prospect of capsize, and storms or being crushed by a freight ship, and the endless too-close proximity of naked, hairy male arses. These frightening-sounding things preoccupied me heavily before we began. You would be a reckless fool if you didn’t reflect on the potential hazards before embarking on a big adventure like this.)

Once we started rowing, out of the harbour, out of sight of land, past the point of no return, something vitally important began to sink in: there was no way off this boat. We were in this for the long haul.

However seasick I was, however scared, tired or bored I may get, there was no way off this boat. I have never done anything in life where, even if I really wanted to, there was no chance whatsoever of quitting and scurrying off to somewhere a little cosier, easier, safer. Out at sea there was absolutely no way to say “I’m done with this”. The only thing to do was row. And, if we rowed, then eventually we would hit land and success.

In other words: it was impossible to fail.

This realisation came upon me gradually, in the same way that you row through the long dark nights and slowly, almost imperceptibly, dawn creeps up on the day. And then, suddenly, it is light once again, the sun broaches the horizon, and the doubts and weariness of the night are blasted away. Appreciating that we could not fail out there in the Atlantic Ocean was a huge moment for me. Because I realised that what I feared the most, what had weighed me down the most before we began as I sat on the jetty staring out at the bloody huge ocean we were about to tackle, what I really feared was just the fear, the uncertainty, the unknown, the prospect of losing control.

Out at sea, knowing now that there was no real way to fail, and certainly no way to quit, was so liberating. I stopped worrying, stopped churning through exhausting negative thoughts, and instead set about trying to savour the experience. Whenever we attempt something bold, we tend to get bogged down by theoretical fears and hypothetical disasters.

Now, it’s much easier to say this than to actually do it (and the ocean row, where you can’t fail even if you want to, is not a normal scenario) but wouldn’t it make all our lives and our plans so much more enjoyable, unshackled and zippy if we just relaxed a little?

Consider the risks, of course. Make sensible contingency plans, of course. But, by and large, just get on with things, and only fret about problems when they actually arise. How quickly and positively we could gallop forward! And, for many of my projects, it’s helpful for me to compare my daily woes with being out in a storm in a leaking boat in the dark, mid ocean, with two incredibly sore buttocks and a diet of shit food for the next month and half…!

Almost every person who reads this is – on a global scale – moderately well-educated, connected and affluent. I cannot speak for everyone, of course, but I’ll use myself as an example specimen: if all of my plans and savings and money-earning avenues failed right this moment, I know that I’d be OK. I know that within 24 hours I would be able to find myself some sort of job. I live in a climate mild enough that even if I had to sleep on the streets for a while I would not die. Therefore, I know that I can earn money, buy food and stay alive. I will not die. If I fail, I will not die.

What then do I fear? Losing money. Losing self-respect. The sneers of peers.

Money I can get more of. My self-respect should remain intact if I gave my all. Therefore it must be the “told you so’s” that hurt the most.

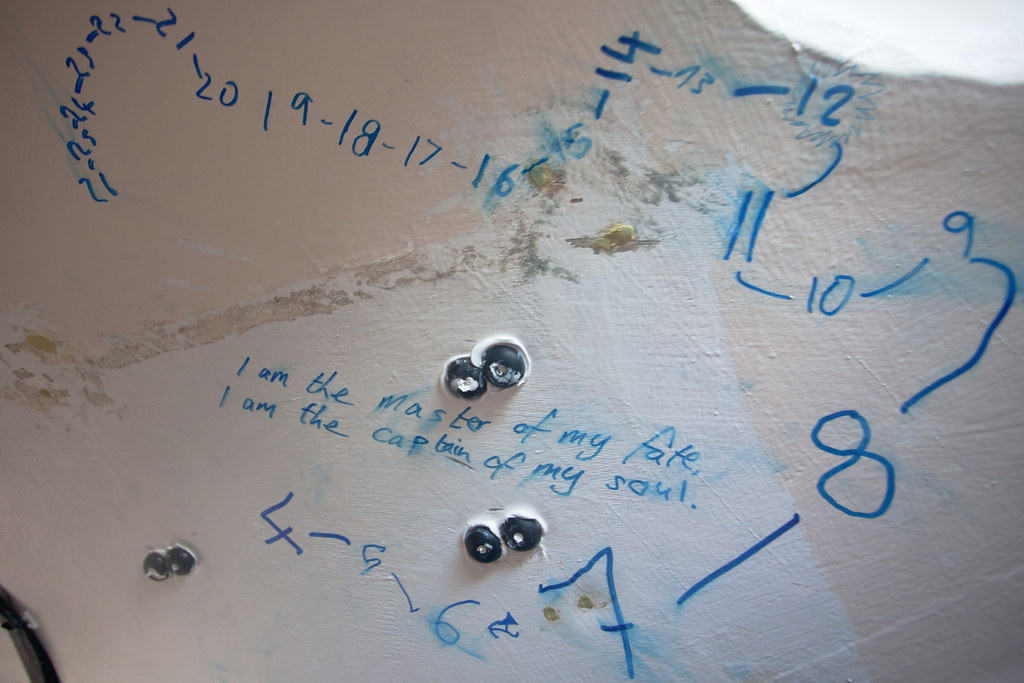

In which case, I need to read, again, the man in the arena and then just crack on with what I am doing.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

It’s an eloquent expression of what’s more pithily known as the “fuck you factor”!

So at the very least, ask yourself this hypothetical question today, “if I had no fear, if I imagine that failure is not an option, what would I do and when would I do it?”

The answer, I suspect, would be “now”.

Let me describe my “now” moment, the moment I summoned up the nerve to commit to doing what I really wanted to do.

I was teaching science at a secondary school near Oxford. I was a trainee teacher, good at the job, and taking my first steps on the interesting, satisfying but conventional ladder towards eventually becoming a Headmaster. A good job, money enough, loads of holidays, and a nice pension. My mum would be happy.

So I was pleased and flattered when the Headmaster at the school offered me a permanent position. I sat down to carefully write my formal letter of reply.

Here are a few excerpts:

“Dear Mr. Walker,

…I would definitely enjoy working here on a permanent basis…

However there is so much to see and do in the world…

If I was to settle into teaching now I am sure that I would enjoy it, but there would always be something gnawing at me…

Therefore I have decided that I am going to go ahead with my original plan to take 2 or 3 years cycling around the globe. I believe that my experiences on the road will only serve to improve my teaching skills when I do decide to return to teaching…

Deep down I know that [teaching is] probably the sensible option. However, even deeper down I know that if I have the chance to do something now and do not take it, I may always regret it.Yours Sincerely…”

Well done, my young me. Well done and thank you!

I climbed onto my bike, waved goodbye to my family, my past life, and a nice, safe, conventional future. I pedalled down the road, and just kept riding. It was over four years before I returned. I cycled across five continents, and I crossed the oceans by boat (By the way – I hitched my way onto boats simply by asking. I spent over a year asking everyone I met whether they might have a boat I could jump on to get me across the Pacific Ocean. Eventually someone said, “yes”. Ask, ask, ask, ask…)

Anyway, cycling round the world is pretty simple, really. You need a bike, a tent, a map, and that’s about it. I quickly realised that my careful months of planning were actually important for one thing only: to give me the confidence to begin. To help me overcome my nerves and the safe, cozy inertia of just keeping on doing what I was already doing. It was an important to reach a tipping point, and to build the most powerful thing of all: momentum. Call it resistance, call it the lizard brain – it’s a common thing this struggle to make yourself begin.

But once you do start, once you get up some steam, you are vastly more likely to succeed than before you take that first tiny step. The first tiny step is massive. Without it, there will never be anything. And not only is it critical, this first little step is also very easy. Don’t worry about all the big things that may go wrong somewhere down the line. Don’t think how long and difficult the journey may be. Just take that first tiny step. That’s all. It’s so easy, if you make yourself look at it without magnifying it with fear.

You probably know your big dream, or at least have an idea. My challenge for you right now is to identify the first tiny step. What is the first thing you need to do to get yourself in motion? And when are you going to take this step by?

Its so easy to fall into the trap of being comfortable, listening to all the people who say it can’t be done, who question why you would take a leap into the unknown. But that gnawing feeling there is something more out there, something still to find. Thanks for the great post Al!

Sometimes you just need to close your eyes and jump. Ready, fire, aim. You can find my first steps here:

http://Www.thebreakfastadventureclub.com

Be Happy – Eat well – Go Explore

James

Your blog posts just keep getting better and better. Well done and thank you.

I have always been very active, from doing all my own own yard work, building porches, sidewalks, or fences, to being in a hiking club and hiking 5-6 miles a day while camping in one of our gorgeous State Parks. Retirement was looming close, I was excited to finally be able to do all things I wanted to do but couldn’t because of my need of full time employment and the paycheck it provided.

Unfortunately, life threw me for a loop, I had cancer. A very rare type of cancer, I might lose my eyesight. While floundering with all that cancer involves, another life threatening event happened, my cancer caused me to have a very minor stroke. Needless to say I was shocked! I’m a widow, how was I going to beat these two huge hurdles by myself?

When I could finally read, I found your website Alstair…what inspiration!

What were the chances of my being able to just camp for a night? I haven’t reach that point yet but my goal is to load up my vehicle, drive to where the Club’s campout and hike will be next month. To be able to put up my own tent and hike a minimum of 3-4 miles with my friends.

By next year at this time, I hope to be well enough to go for a “Micoadventure” all by myself with no need to be with a group in case I become ill while out alone.

Thank you for your posts, I have a long term goal and I believe a reachable one!

Hi Alastair,

It’s great to see you hammering home this point again. I was an armchair dreamer, reading about other people’s adventures, wondering/wishing if/it could be me.

I finally bit that bullet in July 2014 and set off through Europe on my bicycle for the summer before flying to South America.

Then in December 2014 I embarked on my dream, to cycle from Argentina to Alaska. Something I clearly thought I was incapable of. Some two and a half months in I no longer think it is impossible, I just appreciate how hard it is. During the second week, I nearly folded because I thought I wasn’t strong enough, that I had bitten off more than I could chew. I still thought I was playing in someone else’s arena, that I was a pretender.

This is the story http://dennershq.com/cycling/broken-man/

Getting through those few days made me realise I can cycle to Alaska. It’s only myself that will defeat me.

However I would never have left home in July last year if it wasn’t for people like yourself convincing me that I really don’t have anything important to lose.

Thank you once again.

Iain

Cheers Iain!

I wish you well, Barbara!

[…] Need some awesome inspiration to get out and do something right now? Read this now. […]

Well, you need a bike, a tent, and the massive pairs of balls required to quit your good job with no perspective to getting another decent one once back. THAT is the biggest issue to me so far…

Fantastic read yet again, one thing iv noticed when reading yours and your fellow globe conquerors is that whilst leaving all the mundane and monotonous parts of modern life aside, you dont have kids to leave behind. My biggest obstacle is having young children, being a full time dad means i have no job to quit but its a job in itself. And yet the burning desire and the yearning for adventure will not abate. How can one make a choice between parenthood and the calling of adventure. Its a controversial choice and one i shouldnt make. Once again fantastic read! Ps. I feel a micro adventure isnt enough for me.

Hi Thom,

I was in exactly the same situation as you find yourself. Sadly I think that time will be your way around it. I had to wait until my kids were off at university and I had for my finances strong enough to just go for 2 or 3 months. I’m one month into the bike trip across Europe to Turkey from Ireland but I do realise that it wouldn’t have been feasible if the kids were much younger. I’m only 51 now and feel strong enough to do this so I hope you will be patient and the time will come for you.

God speed and I hope and pray it works out for you.

Wow, that’s a powerful post! A real kick in the butt! Alastair, I read your cycling books when I was in school and they helped me shake off the comfortable things that were weighing me down. I got a job at a bike shop, built a bike, built another for my brother, and we rode off into the sunset together! Oregon to AK and back again – it remains the best decision I’ve ever made. But now I’m back where I was before: surrounded by comforts that get in the way of finding out who I am. And you know what? I remember the solution! So here I go again! This August, I’m jumping back in the saddle for a long (10-month?), solo, bike/meditation trip from Alaska to wherever. These trips are vital to us all, but hard to reconcile with the careers/family/bosses. Thanks for helping me find the clarity and confidence to make it a reality.

I always remember you telling me that the hardest part of any trip is stepping out if your front door. Great advice.

[…] – your odds of finishing are darn good. But it’s still not the same as a goal that is impossible to fail at because if you fail you die. I think one of the challenges of endurance sports (and part of the lure)Â is the chance of failure […]

[…] And constantly, constantly, remind yourself that (in Al’s words) ‘if I fail, I will not die’. […]

Wonderful read.

For me, ironically, as I write this now ON social media – I need to cut back on social media to be able to channel my energies towards my studies.

It’s not easy as my online ‘life’ is part of my journey but to see the bigger picture, it has to be done.

The biggest lesson I have learnt so far is that it is not the decision to leap into the unknown that is the most difficult {…it’s felt difficult at the time…} – it is maintaining the dream that you have. Anyone can start. It takes courage to continue.

Thanks for your inspiring words xxxx

[…] you couldn’t fail. That’s never the case in the real world, I know. But just imagine: if there was no way you could fail, what would you do? And when would you begin it? I suspect the idea would be pretty exciting, and you’d begin it […]

Great post pushed me even further into committing to my next objective – Ride the Ridgeway double self supporting off road TT then next year do the Highland Trail 550.

Hi Alastair. I’ve got a good one for you. My grandson just turned 21 and has spent the years since graduation working sporadically and then going off on adventures, mainly hitching to get around. He manages by saving and often staying at workaways. He has had fabulous experiences etc. Problem is his mom is having conniptions that he isn’t following the pattern, off to Uni, a career, etc. My problem is that I pretty much encourage him and would like to get him following your blog, while at the same time maintaining my good relationship with my daughter! Help!

Haha! This sounds familiar…

First of all, I wouldn’t use me as a specific example. There are many, many young people who wander the world for a few years before settling to a normal life. And that is great. I haven’t yet stopped, really, so I’m not a useful case study.

What I would argue is this:

– I learned more from travelling the world than I did at university.

– There is a big and important difference between travel and adventure with purpose, and being an idle bum frittering your time away. (From the outside they may appear to be the same thing!) But I regard this as a crucial part of travel broadening the mind and preparing you for life, as opposed to just wasting time (his Mom’s worry). Perhaps this is where you can offer him some nuanced, subtle mentorship.

– The way the world economy is these days, he will be working until he is 70, at least, before claiming what will by then be a very meagre pension. Look at the big picture. Even if he doesn’t settle down to normal life until 30, he will still have 40 years of respectable work ahead of him. Surely that is enough!

– The way the world works these days, unconventional thinking, self-confidence, entrepreneurial hustle, a broad view, wide connections, and computer literacy are more and more important to more and more careers. I can earn my living anywhere on the planet with WiFi. When I graduated from high school that sentence would not even have made sense, let alone been true. The world is changing fast. Better that we get out and see what is happening rather than being left behind.

This posts may be helpful for him to read:

https://alastairhumphreys.com/young-adventure/

The interviews I did for my book Grand Adventures are a gold mine of lives lived differently but purposefully: https://alastairhumphreys.com/category/blog/grandadventures/

Good luck!

Alastair

I would realy love to join you on an adventure – you will teach me the ropes though as am not as risky

Having the courage to start is always the hardest